After the Storm: Birding in Colombia

By George Oxford Miller

April 15, 2011

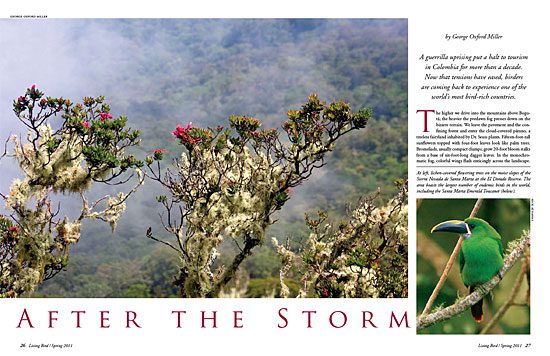

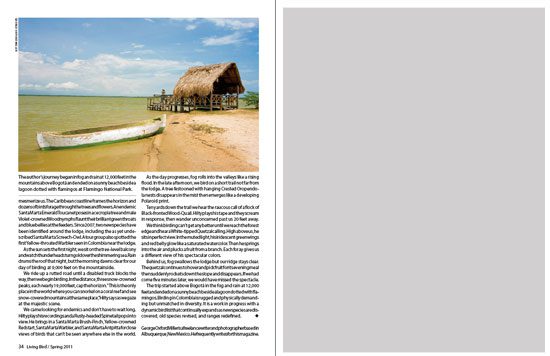

The higher we drive into the mountains above Bogotá, the heavier the predawn fog presses down on the bizarre terrain. We leave the pavement and the confining forest and enter the cloud-covered párano, a treeless fairyland inhabited by Dr. Seuss plants. Fifteen-foot-tall sunflowers topped with four-foot leaves look like palm trees. Bromeliads, usually compact clumps, grow 20-foot bloom stalks from a base of six-foot-long dagger leaves. In the monochromatic fog, colorful wings flash enticingly across the landscape.

The muddy road snakes around precipitous curves on slopes that disappear into a bottomless mist. Roadside Virgin of Guadalupe shrines glow eerily with candlelight in the fog, marking the sites of fatal accidents. The rosary on the rearview mirror swings constantly with the beat of the rocking van. We finally reach the entrance to Chingaza National Park and step into the fog. The melodious calls of hidden birds greet us.

The mist condenses on our binoculars, chills our hands, and bites through our jackets. Then, a flamboyant Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager flits into a bush, and we forget our discomfort.

We walk along a damp path lined with tiny ground-hugging flowers, diminutive relatives of the giant sunflower trees. The biodiversity of the plant families hints at the great diversity of birdlife in Colombia. Some 1,871 species of birds—more than in any other nation—thrive from the country’s snowcapped Andean mountaintops to its humid rainforests, desert scrub, coastal wetlands, and coral beaches.

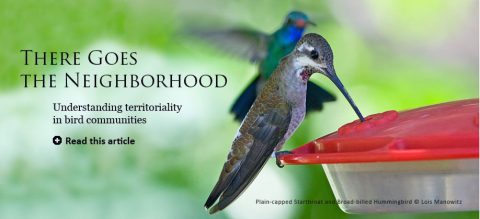

Within minutes of leaving the warm van, we see three Great Sapphirewing hummingbirds in full chase. A pair of Plumbeous Sierra-Finches forages in a bush covered with cascading white flowers, which on closer inspection prove to be lichens. We search for the unusual Bearded Helmetcrest hummer, which lives only above 10,500 feet and feeds on sunflowers with its 1/3-inch bill, but we never get a glimpse.

From the ghostly silhouettes of unearthly plants to the Brown-bellied Swallows that dart through the mist and the unseen hummers, the whole landscape drips with mystery, a fitting analogy for bird watching, and bird research, in Colombia.

“So many birds and so little known about them,” says our tour leader Steve Hilty, from Victor Emanuel Nature Tours (VENT). Hilty, who can identify several thousand birds by call alone, literally wrote the book (with coauthor William L. Brown) on bird watching in this country—A Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Princeton University Press).

“The Andes splits into three ranges in Colombia with deep valleys in between,” he explains. “Each valley and each range is a biological island that developed its own endemic species.”

Since the publication of Hilty’s guide in 1986, more than 160 species have been added to Colombia’s total list. And as more researchers enter the field, the number of new, previously undescribed species grows, as does the number of endemics (currently more than 60).

Hilty began studying for his doctorate in Colombia in 1971, focusing on the foraging behavior of tanagers. He opened up the country to commercial bird watching and led the first VENT tours to Colombia in 1984. He has been leading tours to South America for 35 years.

In 1986, with Hilty’s bird guide published and birding tourism rapidly developing, Colombia seemed destined to become one of the world’s leading birding destinations. But that year, Hilty’s group passed several burned-out military vehicles that had been attacked by rebels, and he decided to cancel future trips. Through the 1990s, guerrilla warfare and abductions paralyzed the nation. In 1998, the leftist group FARC kidnapped four independent bird watchers just a few hours outside of Bogotá. One of them escaped a short time later and the others were released after a month, but the escalating violence slammed the door on all tourism.

After a decade of battle, the current government finally quelled the insurrection. As peace and order returned, the deep valleys, jungles, and mountains once again opened their wonders to visitors. Interest in birds and other biological studies exploded as students and researchers fanned out across the country.

“Colombia is way ahead of other Latin American countries in ornithological studies,” Hilty says. “In the last four years they’ve held two conferences modeled after the American Ornithologists’ Union meetings in the United States. People come from all over the country to present scientific papers and discuss research and conservation issues. More than 300 students and professors attended the last one.”

Because of his extensive field research in Colombia and his experience leading tours throughout South America, Hilty was the keynote speaker at the first conference.

“For the decade during Colombia’s problems, I thought I’d never be able to come back with groups,” Hilty says. “So it’s exciting to return and see all the changes in conservation and eco-tourism. I worked for 15 years basically alone in birding tourism. Now I can learn a lot from the young Colombians. They scout all over the country and share their findings on an Internet group of about 600 birders.”

Hilty leads our tour with Luis Eduardo Urueña, an expert birder and researcher who heads Manakin Nature Tours. While studying Painted and Todd’s parakeets, which eventually were classified as separate species, he located several new sites with rare birds that our group visits. Having a Colombian ornithologist along who has worked in many of the localities eases the logistics and adds a cultural dimension to the tour.

“I don’t see any reason why bird watching shouldn’t really explode in Colombia in the next few years,” Hilty says. “The biggest problem is lack of infrastructure. ProAves has developed the model for ecotourism with ecolodges in their preserves.”

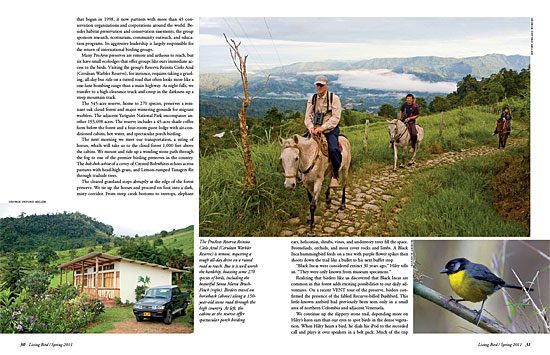

ProAves is the major conservation organization in Colombia and manages 15 preserves for threatened and endemic species; they welcome birding groups. A nongovernmental organization that began in 1998, it now partners with more than 45 conservation organizations and corporations around the world. Besides habitat preservation and conservation easements, the group sponsors research, ecotourism, community outreach, and education programs. Its aggressive leadership is largely responsible for the return of international birding groups.

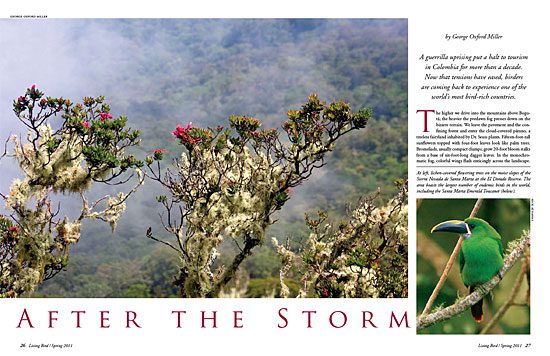

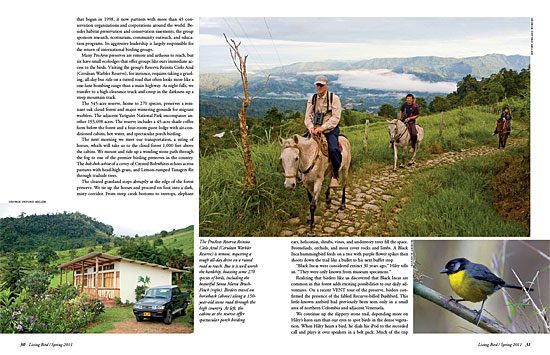

Many ProAves preserves are remote and arduous to reach, but six have small ecolodges that offer groups like ours immediate access to the birds. Visiting the group’s Reserva Reinita Cielo Azul (Cerulean Warbler Reserve), for instance, requires taking a grueling, all-day bus ride on a rutted road that often looks more like a one-lane bombing range than a main highway. As night falls, we transfer to a high-clearance truck and creep in the darkness up a steep mountain track.

The 545-acre reserve, home to 270 species, preserves a remnant oak cloud forest and major wintering grounds for migrant warblers. The adjacent Yariguíes National Park encompasses another 193,698 acres. The reserve includes a 45-acre shade coffee farm below the forest and a four-room guest lodge with air-conditioned cabins, hot water, and spectacular porch birding.

The next morning we meet our transportation, a string of horses, which will take us to the cloud forest 1,000 feet above the cabins. We mount and ride up a winding stone path through the fog to one of the premier birding preserves in the country. The bob-bob-white of a covey of Crested Bobwhites echoes across pastures with head-high grass, and Lemon-rumped Tanagers flit through trailside trees.

The cleared grassland stops abruptly at the edge of the forest preserve. We tie up the horses and proceed on foot into a dark, misty corridor. From steep creek bottoms to treetops, elephant ears, heliconias, shrubs, vines, and understory trees fill the space. Bromeliads, orchids, and moss cover rocks and limbs. A Black Inca hummingbird feeds on a tree with purple flower spikes then shoots down the trail like a bullet to his next buffet stop.

“Black Incas were considered extinct 30 years ago,” Hilty tells us. “They were only known from museum specimens.”

Realizing that birders like us discovered that Black Incas are common in this forest adds exciting possibilities to our daily adventures. On a recent VENT tour of the preserve, birders confirmed the presence of the fabled Recurve-billed Bushbird. This little-known antbird had previously been seen only in a small area of northern Colombia and adjacent Venezuela.

We continue up the slippery stone trail, depending more on Hilty’s keen ears than our eyes to spot birds in the dense vegetation. When Hilty hears a bird, he dials his iPod to the recorded call and plays it over speakers in a belt pack. Much of the trip involves “tape-and-wait” birding as the birds cautiously make their way to the playback and then curiously hop around in the thick vegetation. Rarely do we miss a species.

After lunch on the side of the trail, Hilty gathers his equipment and dials in a birdcall we haven’t heard. “Let’s go find Parker’s Antbird,” he says.

Parker’s Antbird did not exist until 1997—at least not in the birding books and ornithology journals. Of course, the bird given that name had been foraging through the mountain undergrowth for millennia. But like many birds in understudied places throughout Latin America, it was lumped with its look-alike, the lower-elevation and easily accessible Dusky Antbird.

We wander a few meters down a side trail, which quickly fades into the vegetation. Hilty plays the bird’s call. Almost immediately, a flash of feathers scoots through the brush. After a few more calls, the antbird pops into view. Soon its mate joins the show. Hilty skillfully plays the tape until we all have full-frame views of the elusive bird. He makes it look all too easy to see a species that until recently had escaped scientific notice.

Ted Parker, the namesake for the antbird, worked for Conservation International, led tours for Victor Emanuel, and was a member of the administrative board of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. One of the world’s best field ornithologists, Parker could identify more than 4,000 birds solely by call. He contributed more than 10,000 recordings to the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library archives before his untimely death in a plane crash in Ecuador in 1993.

Parker’s Antbird wasn’t discovered in the field, Hilty tells us. One of Parker’s friends, Gary Graves (curator of birds at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History), began looking at the differences in study skins of antbirds collected at different elevations. The more he looked at the Dusky Antbird, the more differences he found. He finally speculated that two species existed and that the higher-elevation population would have a different call. Field research proved him right, and he named the new species after Ted Parker.

Listening closely to vocalizations is the best way to identify birds in dense tropical forests, and sometimes it can lead to memorable surprises.

On a VENT jungle and river cruise tour on the Orinoco River in 1998, Hilty heard a strange call.

“We approached an island on the Colombia-Venezuela border and 5,000 Fork-tailed Flycatchers exploded into the air,” he says. “Then we heard a spinetail that I didn’t recognize. When we spotted the bird, it looked like a Pale-breasted Spinetail but it didn’t respond to the playback. I recorded its call and later played it to a Pale-breasted, and it didn’t respond either. The bird proved to be a completely different species. We called it the Rio Orinoco Spinetail. The Auk published the description in 2009.”

After seeing the Parker’s Antbird, we continue up the trail in a slight drizzle. Soon a piercing call stops Hilty in his tracks. He hasn’t a clue what it is. He records the call and plays it back. We hear a response 20 meters to the right, then suddenly to the left. For 30 minutes we listen and watch. Finally, Hilty gives up. Later that evening he confesses, “I think it was a frog.”

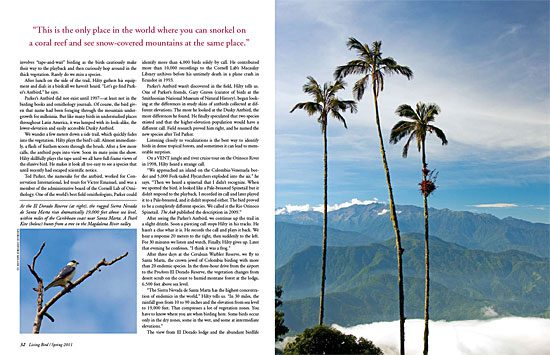

After three days at the Cerulean Warbler Reserve, we fly to Santa Marta, the crown jewel of Colombia birding with more than 20 endemic species. In the three-hour drive from the airport to the ProAves El Dorado Reserve, the vegetation changes from desert scrub on the coast to humid montane forest at the lodge, 6,500 feet above sea level.

“The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta has the highest concentration of endemics in the world,” Hilty tells us. “In 30 miles, the rainfall goes from 10 to 90 inches and the elevation from sea level to 19,000 feet. That compresses a lot of vegetation zones. You have to know where you are when birding here. Some birds occur only in the dry zones, some in the wet, and some at intermediate elevations.”

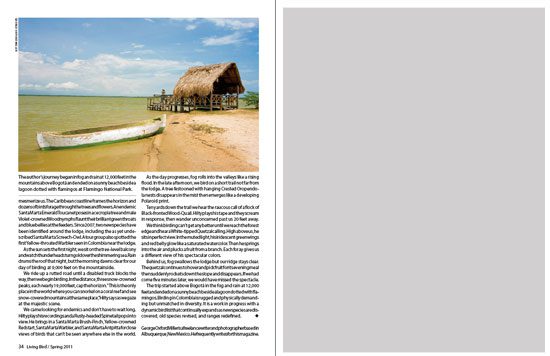

The view from El Dorado lodge and the abundant birdlife mesmerize us. The Caribbean coastline frames the horizon and dozens of birds forage through the trees and flowers. An endemic Santa Marta Emerald Toucanet poses in a cecropia tree and male Violet-crowned Woodnymphs flaunt their brilliant green throats and blue bellies at the feeders. Since 2007, two new species have been identified around the lodge, including the as yet undescribed Santa Marta Screech-Owl. A tour group also spotted the first Yellow-throated Warbler seen in Colombia near the lodge.

As the sun sets the first night, we sit on the tree-level balcony and watch thunderheads turn gold over the shimmering sea. Rain drums the roof that night, but the morning dawns clear for our day of birding at 9,000 feet on the mountainside.

We ride up a rutted road until a disabled truck blocks the way, then we begin birding. In the distance, three snow-crowned peaks, each nearly 19,000 feet, cap the horizon. “This is the only place in the world where you can snorkel on a coral reef and see snow-covered mountains at the same place,” Hilty says as we gaze at the majestic scene.

We came looking for endemics and don’t have to wait long. Hilty plays his recordings and a Rusty-headed Spinetail pops into view. He brings in a Santa Marta Brush-Finch, Yellow-crowned Redstart, Santa Marta Warbler, and Santa Marta Antpitta for close views of birds that can’t be seen anywhere else in the world.

As the day progresses, fog rolls into the valleys like a rising flood. In the late afternoon, we bird on a short trail not far from the lodge. A tree festooned with hanging Crested Oropendola nests disappears in the mist then emerges like a developing Polaroid print.

Ten yards down the trail we hear the raucous call of a flock of Black-fronted Wood-Quail. Hilty plays his tape and they scream in response, then wander unconcerned past us 20 feet away.

We think birding can’t get any better until we reach the forest edge and hear a White-tipped Quetzal calling. High above us, he sits in perfect view. In the muted light, his iridescent green wings and red belly glow like a saturated watercolor. Then he springs into the air and plucks a fruit from a branch. Each foray gives us a different view of his spectacular colors.

Behind us, fog swallows the lodge but our ridge stays clear. The quetzal continues to hover and pick fruit for its evening meal then suddenly rockets down the slope and disappears. If we had come five minutes later, we would have missed the spectacle.

The trip started above Bogotá in the fog and rain at 12,000 feet and ended on a sunny beach beside a lagoon dotted with flamingos. Birding in Colombia is rugged and physically demanding but unmatched in diversity. It is a work in progress with a dynamic bird list that continually expands as new species are discovered, old species revised, and ranges redefined.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you