First Look at an Ancient Field Guide

by Hugh Powell; Illustration by Michael DiGiorgio

April 15, 2010

One Monday in February, Richard Prum was waiting for an eggplant pizza and eagerly describing a dinosaur called Anchiornis huxleyi. Prum and a team of colleagues had just deciphered the colors of the animal’s feathers, and the finding held insights about why feathers might ever have evolved in the first place.

“It was a terrible-looking fossil, but it was the best we could get—basically Jurassic roadkill,” he said. Its four limbs were splayed awkwardly across the rock, head shattered, tail missing. But the 150-million-year-old Chinese limestone surrounding it was fine as parchment, and the dinosaur’s feathers were etched as clearly as a tombstone rubbing.

Prum, a Yale evolutionary biologist and birder, was visiting the Cornell Lab as part of our Monday-Night Seminar series. His team’s description of Anchiornis’s color scheme, right down to the rusty spangles on its cheeks, had come out on Sciencemagazine’s website the week before.

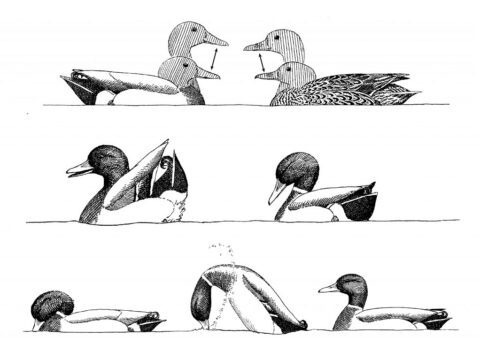

Looking at the elegant painting Prum commissioned for the article is like flipping backward through an ancient field guide. Way back, before dodos, mammoths, even T. rex, sits this striking little roadrunner-shaped dinosaur. The sooty-black creature had dazzling black-and-white fringes on its legs, as if it wore chaps, and a bright chestnut crest worthy of a Red-breasted Merganser. It looked remarkably like a bird, but it wasn’t. It had a snout instead of a bill, a sharp crescent for a thumb claw, and decidedly non-aerodynamic feathers.

Prevailing ideas hold that feathers probably evolved in service of one of their two main present-day duties, flight and insulation. But this flightless dinosaur’s bright markings highlight another key role, Prum said. The bold colors of early feathers might have helped with communication and in visual displays, he suggested.

The discovery began with a cloud of ink trapped around a fossilized squid. Yale graduate student Jakob Vinther realized that under an electron microscope, impressions of pigment from the squid ink were still visible in the fossil. At 30,000x magnification, they looked like fields of ellipses, some fat as jelly beans, others slender as a fountain pen. Paleontologists had noticed these before, but until Vinther saw them in ink (which is inky because it is full of pigment), the prevailing explanation was that they were bacteria that had fed on the rotting carcass.

Present-day birds use these same pigment packets, called melanosomes, in their earth-toned feathers. So Vinther, Prum, and colleagues guessed they could learn something of Anchiornis’s color by comparing its melanosomes with those of living birds. They fired up the electron microscope and analyzed feathers of 30 birds, from Acorn Woodpeckers to Zebra Finches.

They learned that the different melanosome shapes corresponded to different colors. Jelly-bean-like melanosomes yield brown to red-brown; fountain-pen shapes indicate gray to black. The team developed an analysis that predictedAnchiornis’s melanosome colors with 90-percent confidence. They had a sampler palette for dinosaur feathers.

“So right now we know of five dinosaur colors,” Prum said, counting them off on his fingers. “Black, gray, brown, red-brown, and white.” For a lifelong birder, it’s a thrill Prum never expected. “I got to write the first page in the field guide of the dinosaurs,” he said. “And for a kid who grew up as a birder with the Chan RobbinsGolden Guide, that’s about as transformative an experience as you can have.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you