Birds of St. Matthew Island, the Most Remote Place in the United States

Story by Irby Lovette; Photography by Andy Johnson

March 31, 2019From the Spring 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

This project was conducted in cooperation with the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge and made possible through the support of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

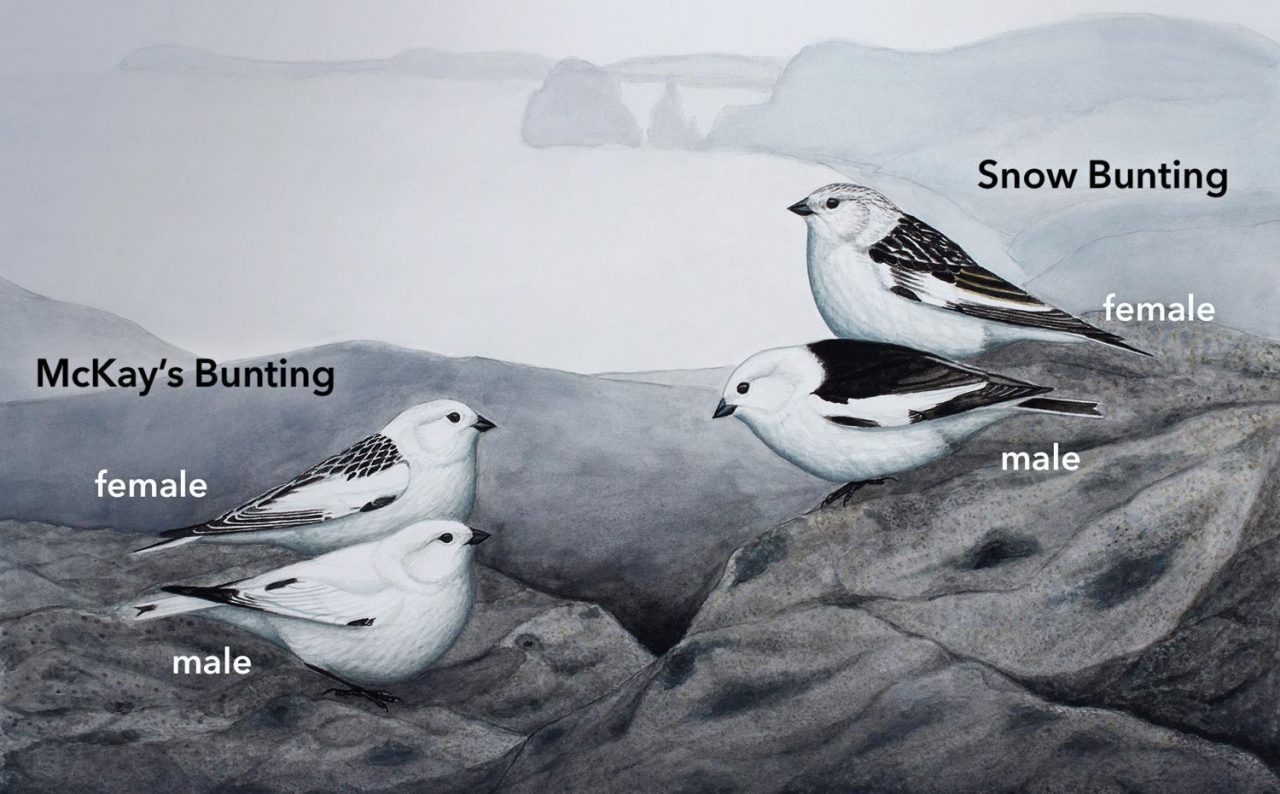

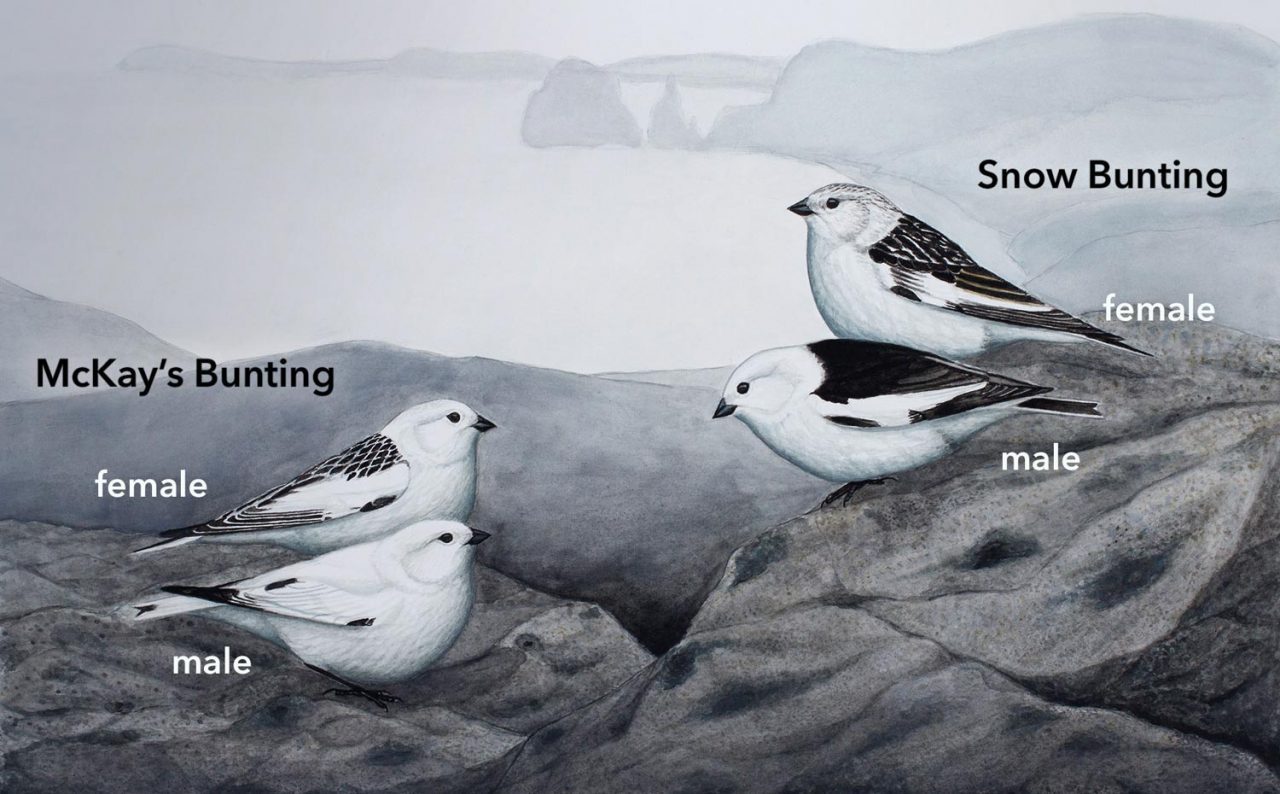

With a flash of black wingtips against its spotless white body, my first-ever McKay’s Bunting flies along the beach even before our boat touches land. This Alaskan bunting is a grail-bird species seen by very few birders, or even ornithologists. That’s because in visiting this bunting’s island, we’re venturing to a place very few people have ever been. The remoteness of its only breeding place has made McKay’s Bunting the least-studied bird species endemic to North America. Many enigmas surround this little-known bird and its fog-shrouded homeland, St. Matthew Island, which rises out of the Bering Sea more than 200 miles off the northwest coast of mainland Alaska. The Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library houses 380,000 audio recordings of 8,700 species of birds, but there was no recording of a McKay Bunting’s mating song—until our team’s visit in the early summer of 2018.

Our mission is to fill gaps in knowledge about the biology of St. Matthew and its animals. Our Zodiac is piled high with waterproofed bags of research and film gear as it delivers two of us from Cornell University—myself, a professor of ornithology, and Andy Johnson, a filmmaker and producer from the Cornell Lab’s conservation media department—to join three wildlife biologists already camped on the island to conduct bird surveys. We will work together as one team in the coming weeks to study and document the spectacular wildlife of this isolated wilderness. While our main focus is on the breeding ecology of McKay’s Buntings, a close second among our scientific targets is the distinctive race of the Rock Sandpiper—a subspecies, by current classification—that breeds only here and on the Pribilof Islands to the south. And in every spare moment we will study the many other birds and special creatures that inhabit this rarely visited isle.

This is Andy Johnson with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. I’m on St. Matthew Island, Alaska, by some measures, the most remote wilderness in the country. It’s an uninhabited outpost of jagged pinnacles, talus slopes, and tundra valleys that give way to sheer cliffs. Scientists are documenting rapid changes across the Arctic, and for the first time in six years, the US Fish and Wildlife Service sent a team here for a month to collect long-term data on changes to the island’s bird life.

Stephanie Walden and Bryce Robinson are working for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. And Rachel Richardson is from the US Geological Survey’s Alaska Science Center. They’re here to study and resurvey populations of the Pribilof Rock Sandpiper and the McKay’s Bunting. My colleague from the Cornell Lab, Irby Lovette, and I are here to film the birds and record their songs.

This is the only place on Earth where McKay’s Buntings nest. (gentle music) The Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge is a collection of protected lands spread across coastal Alaska. Together, the refuge provides habitat to around 80% of Alaska’s nesting seabirds. St. Matthew island sits isolated more than 200 miles from the mainland. It stretches 30 miles long and just a few miles across and it’s one of the first areas to be protected by the National Wildlife Refuge System.

For the seabirds arriving here, St. Matthew is critical. (birds chattering) The coastal talus and cliffs offer safe nesting sites. (bird chirping) Colonies are supported by cold, nutrient-rich waters, full of plankton and small fish. It’s perfect habitat to breed and raise young. One of these colonies is just a mile north of our camp at the base of the Glory of Russia Cape.

(birds chirping) We’ve set up a blind where soft sediments collapse into a precarious slope of loose boulders. And at dusk, we’re surrounded by laughing, croaking calls. (birds chirping and chattering) Tens of thousands of Least and Crested Auklets stream in from the open water to gather outside the deep crevices. It’s still early for nesting, but their spectacular courtship is already on display. Both males and females sport a loose crest of feathers on their foreheads, and it’s amazing to watch them clamoring together, flaunting their plumes for potential mates. (gentle music and birds squawking)

Working here is exhilarating and exhausting. Since researchers only visit every five to seven years, we’re collecting as much data and footage as we can. And with 20 hours of daylight, we’re caught in a tireless delirium. Every moment is valuable and we’re constantly on the lookout for McKay’s Buntings and Rock Sandpipers. We find the sandpipers in wide tundra valleys foraging for insects out in the open. (birds chirping and chattering) But their mates are a little tougher to see. They sit frozen and perfectly camouflaged in the lichens and mosses, brooding their chicks.

(bird chattering) Less than a hundred yards away, Long-tailed Jaegers are also nesting and patrolling the tundra. (gentle music and birds chirping) They’ll eat sandpiper eggs and young. So to find cover, these exposed chicks need to move quickly just hours after hatching. (birds chirping) They’re better hidden in nearby sedge meadows. (bird chattering)

Hiking higher onto the island’s foggy slopes, we find our other target, the McKay’s Buntings. (birds chirping) They’re most abundant here in fields of volcanic talus darting through the rocks in pairs. The buntings are nicknamed snowflakes, and I can see why.

(birds chirping) It’s hard to predict, but males perform this beautiful arcing display flight, floating down to advertise a choice crevice. And if they’re lucky, an interested female will inspect the site’s potential for building a nest. (birds chirping) In our four weeks here, we find nests across the island, watching flecks of white disappear into the dark rocks. (birds chirping)

We’re noticing the chicks stay hidden in the nest for nearly two weeks after hatching, much longer than expected for a small songbird. It seems like the buntings are taking full advantage of the safety in these deep crevices. Once the chicks finally leave, they’re already capable fliers. McKays Bunting and Rock Sandpiper have adapted to their island over millennia. (bird chattering)

But they face an uncertain future. In spite of St. Matthew’s extreme isolation, we’re noticing signs of just how much is changing today. The region is in its fourth year of a marine heat wave. And the extent of winter sea ice is at record lows. (birds chattering) Warming waters are likely pushing marine prey out of reach for seabirds and some Arctic colonies have recently seen massive and repeated breeding failures. On the beach near camp, Stephanie has counted nearly 250 carcasses in a 300 meter survey. All signs that worrying trends in seabird productivity and mortality across the Bering Sea may be affecting St. Matthew as well.

But for us, it’s a small land mammal that represents how quickly change can take hold here. With a warming Arctic, red foxes have swept north across the mainland, outcompeting resident Arctic foxes. They were first spotted here on St. Matthew in 1966. At that time, we would have seen Arctic foxes across the island. (gentle music) But today, in the distance, we glimpse just one trotting over the tundra. It feels like a ghost of the island’s past.

St. Matthew is part of a Bering Sea ecosystem that’s in rapid flux, losing the ice that has defined the existence of its inhabitants for millennia. (bird chattering) But for me, this expedition was also a chance to witness firsthand the symptoms of a changing Arctic. There’s no telling what future expeditions will find here but it will certainly be different from what we are seeing. Still, we’re leaving St. Matthew in awe of what remains. (birds chirping and cawing)

End of Transcript

Our voyage here took three days, by plane and boat. After a PenAir flight from Anchorage to the far-flung Pribilof island of St. Paul—itself famous for its rich seabird and fur seal colonies and beloved by intrepid birders for attracting serendipitous avian vagrants from Asia—we reached the end of the commercial travel industry’s reach into the Bering Sea. From here Andy and I relied on the support of a large team from the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, including the intrepid crew of its research vessel the R/V Tiglax, which we boarded for a 30-hour ride into a region of the northern Pacific Ocean that’s notorious for its storms. We expected a churning, fog-enshrouded roller-coaster ride, but instead we are happily surprised by calming seas and clearing skies as we approach St. Matthew and its two smaller satellite islands, Pinnacle and Hall.

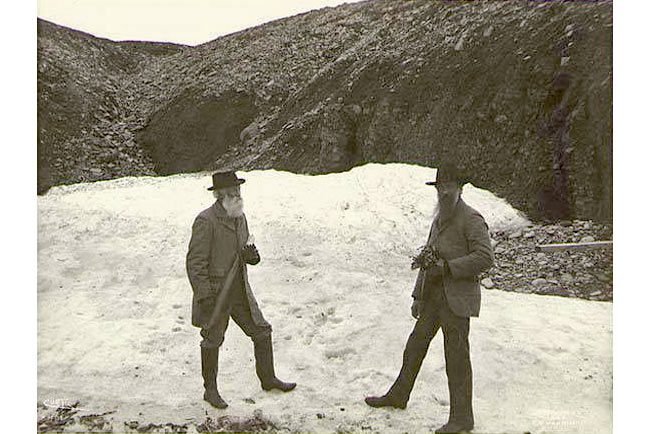

Andy and I are not the first Cornellians to venture here. Back in 1899, Louis Agassiz Fuertes (the famous bird artist and naturalist) partnered with his good friend Dr. Arthur Allen (founder of the Cornell Lab) to visit St. Matthew as part of a scientific voyage organized by Edward Harriman, a Gilded Age railroad baron for whom exploration was a hobby and a passion. Some of the most prominent field biologists and conservationists of that era, including John Muir and George Bird Grinnell, were also on board the Harriman Expedition. Their collective observations of the seabirds nesting on St. Matthew helped motivate its preservation, and in 1909 this remote little archipelago was set aside as one of the very first federal Bird Reservations, a precursor to its current status as a wilderness unit within the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

As the Tiglax (pronounced TEK-LAH, the Aleut word for “eagle”) turns to coast along St. Matthew toward our drop point, we gain an expansive view of the island’s green tundra valleys, brilliant hillside snowfields, eroding cliff faces, and corrugated mountains. St. Matthew is narrow, about 20 miles long on its north-to-south axis but only three to five miles wide. It is bookended by higher mountains on both headlands, while the intervening coastlines alternate between tall cliffs and sandy beaches backed by shallow lagoons.

Fuertes himself spent only one day on land admiring the McKay’s Buntings, whose nesting grounds had been discovered a few years previously. Fuertes was a skilled field scientist as well as an artist; our vertebrate museum at Cornell still boasts a handful of McKay’s Bunting study skins that he prepared during that visit. Yet Fuertes’s journal notes from that day telegraph his appreciation for the buntings as living creatures. He repeatedly refers to them by their avian nickname of “snowflakes,” alluding both to their nearly all-white plumage and to the breeding display of the males, which fly up into the air and then sing as they drift slowly to the ground with their white-and-black wings held outstretched in a rigid V-shape.

In the coming weeks we will join Fuertes in the rarified club of the very few ornithologists to have witnessed this bunting’s snowflake display.

Rendezvous on St. Matthew Island

As the Tiglax disappears around the northern St. Matthew headland, we know it will be a month before the boat returns to retrieve us. We are on our own in the most remote place within any of the 50 United States.

The “we” includes not just Andy and me, but three wildlife biologists–Rachel Richardson from the United States Geological Survey Alaska Science Center, and Bryce Robinson and Stephanie Walden, volunteers for the USFWS Alaska Maritime Wildlife Refuge. As our Zodiac makes it through the surf line, they all wear big smiles as they wade over to help us move our gear to the dry part of the beach. They arrived on St. Matthew the previous week to begin their work by running bird surveys, hiking back and forth across the entire island, carefully documenting every bunting and sandpiper that they encountered.

Over the following month, these three scientists will continue to make the most of their time on the island.

“Other people, they don’t come here,” Richardson tells us. “We are taking advantage of the opportunity to be out here collecting these data now, because it’s unknown when the next expedition will be, when the next people will even set foot on this island.”

It’s a grueling routine, but it’s important, she says.

“I like getting up in the morning knowing that I’m heading out to do good work,” she says, noting that the last surveys of breeding McKay’s Buntings and Rock Sandpipers were conducted 15 years ago. “If we don’t come back out and assess where their populations sit, then we may miss when there’s a crash. You could essentially lose the species and not know why.”

Andy and I have come to document the island and its wildlife through audio and video recordings, which will be used in conservation outreach and research and archived in the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library. Although Andy is just a few years out of college, he already has extensive experience working in arctic settings for the Cornell Lab’s multimedia productions. For my part, I’m a Cornell ornithology professor tasked with interpreting the biology of the buntings and their environment. I’m also here to serve as Andy’s assistant—a full role-reversal, because I was Andy’s faculty advisor when he was a Cornell undergraduate. All teachers know that one of our field’s great joys is following former students as they master their profession, but we rarely get to see it unfold in action. On this trip to St. Matthew, as Andy’s tripod-carrier, I have a front-row view of his talent in documenting wildlife and their behaviors.

Since McKay’s Buntings breed only here, any changes happening on St. Matthew will dictate the fate of the entire species. This year’s island-wide bunting census is only the second such effort. The initial survey in 2003 estimated the total bunting population at roughly 30,000 birds—welcome news at the time, since earlier guesses had pegged the number of buntings at only a few thousand. Sitting around our communal cookstove on our first St. Matthew evening, Richardson tells us that they are finding buntings nesting all across the island.

Andy and I can’t wait to go exploring in the morning. The rocky ridgelines and high snowfields above our camp draw us both upward on different trajectories, and soon Andy’s bright red jacket is just a distant spot against the green mosses of the hillside. I can see him following birds through his lifted binoculars, and I wonder what he has discovered on those higher slopes.

There are plenty of McKay’s Buntings to attract my own attention, and I find my first bunting nest while following a rushing stream up a rocky valley. Even from a distance, it is easy to spot, because the bright white male bunting flies up in his snowflake display every time his mate nears the nest, and then he keeps singing as he perches on a nearby boulder.

This male’s display is on repeat every few minutes as the gray-speckled female returns with a beak full of nesting material, which she carries into a crevice within a loose scree of basketball-sized rocks. She must be almost finished with her nest-building since she is gathering fluffy white gull feathers to line her nest cup. In a moment while the female is away, I peer into the crevice in the hope of seeing her full nest, but it is tucked so deeply into the tumbled rocks that I can glimpse only an inch or so of the rim.

Instead, I pull out my GPS unit so that I can pass these exact coordinates along to the biologists. They will add it to their regular nest-checking circuit, visiting every few days to follow the fate of the eggs and chicks. Their nest-checking equipment includes a long fiberscope that they snake down into crevices to view the nests and their contents, counting first the eggs and later the number of chicks. The bunting chicks are easy to count at the beginning, because they gape wide while begging at the fiberscope as if it were a parent bird delivering food. After a week or so the chicks become wiser, and they remain snuggled quietly in their nest when the scope enters their cavity. These particular bunting parents succeed in fledging all four of their chicks from this nest, and by the time we leave the island in July this same female will be lining a new nest cup as she initiates a second round of breeding.

When I ascend the ridge to ask Andy what he has found, he points out a group of resident Gray-crowned Rosy-Finches feeding on the edge of a snowbank. Andy has also found a Rock Sandpiper cup nestled within the mosses on the very crest of the ridge. We sit nearby and share a granola bar while admiring the spectacular 360-degree view enjoyed by this pair of incubating sandpipers. This moment is a bit deceptive, since we will never see that entirely cloudless view again during our weeks on this usually foggy island. And, sadly, this particular sandpiper nest will make it only halfway through incubation before a hungry fox discovers the four eggs.

A Seabird Layer Cake

From inside my tent, I can look down a sandy beach at the edge of a clear stream that drains a wide tundra valley. One morning Andy and I take a short stroll to the south end of the beach and look out at a massive offshore sea-stack that seems like a layer cake of breeding seabirds.

Close to the base are pairs of Pelagic Cormorants constructing messy seaweed nests, while narrow ledges on the higher cliffs support pairs of Northern Fulmars and Black-legged Kittiwakes. The green slope above the cliffs is riddled with Tufted Puffin nesting burrows, from which pairs of adult puffins emerge to dot this slope in the low light of late arctic evenings. The very top of the sea-stack is owned by about a dozen pairs of pale white Glaucous Gulls. We had been hoping to find this species breeding here, because St. Matthew is the most southerly breeding site of this impressive northern gull, the second-largest gull species in the world.

There’s another seabird colony at the opposite end of the beach where a massive section of the seacliff has tumbled down to form a wide talus slope of large boulders embedded within a treacherous matrix of soggy clay. Three species of auklets—Least, Parakeet, and Crested—nest deep among these rocks, but our first noontime foray here is a disappointment because only a few birds are visible. Still, we get hints that more birds are present than we can see, as we can hear the otherworldly calls of unseen auklets coming from deep crevices as we scramble among the boulders.

The few visible auklets are skittish and fly away if we approach, so Andy and I find a relatively flat boulder just large enough to support a small photography blind. Securing the blind in the gusty wind is a challenge, but after stringing many guy-ropes to nearby rocks we depart with reasonable confidence that the blind will survive. We make plans to return in the evening when the auklets might be more active.

By 11 p.m., the long arctic summer day is turning dusky, and the sun will soon set for a few hours. Andy and I take turns crawling into the blind to witness an auklet colony transformed; little seabirds are everywhere, displaying on every rock and wheeling overhead in noisy flocks. This is clearly the auklets’ hour to display and find mates. Lines of diminutive Least Auklets queue together, squeaking and squabbling and sometimes disappearing by the pair into holes in the talus. Groups of Parakeet Auklets dominate the tops of the flattest rocks, showcasing their bright orange bills. Most conspicuous of all, clusters of Crested Auklets call back and forth to one another; even though I try to maintain my composure as a serious professional ornithologist, I cannot help but laugh at their utterly comical crests and ridiculous display behaviors. Andy and I later agree that Crested Auklets are kin to the creature Dr. Seuss would have invented if he drew an arctic seabird.

St. Matthew’s auklet colonies have never been closely monitored, but for many decades refuge scientists have closely tracked the breeding success of seabirds at colonies in the Pribilof and Aleutian islands to the south. Those other Bering Sea colonies have experienced an unusually large number of poor breeding cycles in recent years, particularly in the Pribilofs, where the famed seabird cliffs have fledged very few murres, kittiwakes, puffins, or auklets in the past several summers.

Concerns are rising that the changing climate of the Bering Sea region is causing sudden and cascading changes to this region’s ocean food web, and that the seabirds at the top of that web are particularly vulnerable to losses of their main food resources. The exuberance of birds in these St. Matthew auklet colonies suggests that there are still plenty of adults ready to serve as breeders as long as these seas continue to produce the abundance of crustaceans and zooplankton required to feed millions of auklets.

Mammals of St.Matthew Island

While birds are the focus for our research team, over the years some of the most dramatic biological dramas on St. Matthew have involved its mammals. The smallest mammal on the island is a species found only here, the St. Matthew singing vole, named for its habit of standing at the opening of its tunnel while singing a cricket-like medley of high-pitched tones. These cute little animals live in loose colonies, and in the dusky light of the long arctic evenings several voles in a colony often call back and forth in chorus.

At other times they chirp out alarm calls to warn against possible approaching threats, including humans. As we walk across the tundra we are surrounded by a moving auditory halo of vole squeaks. These sounds are so ever-present that after a few days of habituation we stop noticing them, but whenever we pull out a microphone to record a singing bunting or sandpiper, our headphones remind us that the voles are always there, chirping away in the background.

In some years the singing vole chorus goes silent. Like other arctic voles, they undergo boom–bust population cycles. A century ago a frustrated mammologist spent an entire week trying to trap these voles and encountered only a single animal. That must have been a vole bust year. We clearly have arrived during a boom year, because the voles and their trails are everywhere. By placing a tiny microphone at the opening of an active tunnel, we obtain recordings from just an inch or so away from one vole virtuoso; these recordings will soon be archived in the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library, and are likely the first ever made of this little-seen species.

While working at the far end of our valley, Andy and biologist Bryce Robinson have glimpsed a pair of skittish Snowy Owls preying on voles, but the voles’ most ubiquitous avian predator is the Long-tailed Jaeger. A family of jaegers nested near our campsite. One day we make the short walk to watch the jaeger family and witness a somewhat gruesome sight as the adult jaegers regurgitate voles for their two growing chicks. At first, the tiny jaeger chicks can swallow only small morsels, so one parent jaeger disgorges a chunk of partially digested vole and then holds it in its hooked bill while the other parent delicately picks off scraps of meat and feeds them to its offspring.

The red fox family that is denning a few meters from our cook-tent enjoys a more eclectic menu containing both voles and seabirds, particularly auklets and puffins. The antics of the four kits keep us entertained around camp, and we often see the adults hunting on the tundra or scavenging along the seacoast, then bringing their prey back to feed their family. Yet we know that the presence of these red foxes reflects broad human-caused changes in the arctic environment. Until recently it was arctic foxes—not red foxes—that were common on St. Matthew. My friend Kevin Winker, an Alaskan ornithologist who did extensive bird research here several decades ago, had warned me that the arctic foxes here had the nasty habit of scent-marking everything in their territories, especially tents and unattended backpacks.

For better or worse, our gear has not been fouled by arctic foxes because they are now nearly gone from St. Matthew. All across the continent, red foxes are steadily moving north with the warming climate, and where the species meet, the larger red foxes tend to dominate the smaller arctic foxes, either killing them or driving them away. This dynamic played out very rapidly on St. Matthew after red foxes crossed the winter sea ice to colonize the island in the mid-1990s. Before our visit, the most recent surveys had found only red foxes on St. Matthew, although arctic foxes remained on smaller Hall Island. Andy and I do a double-take when we spot a small white-and-black mottled fox loping across the tundra in the low light of one late evening. Although Andy’s footage clearly documents this arctic fox, we both felt like we had seen a ghost of the island’s past.

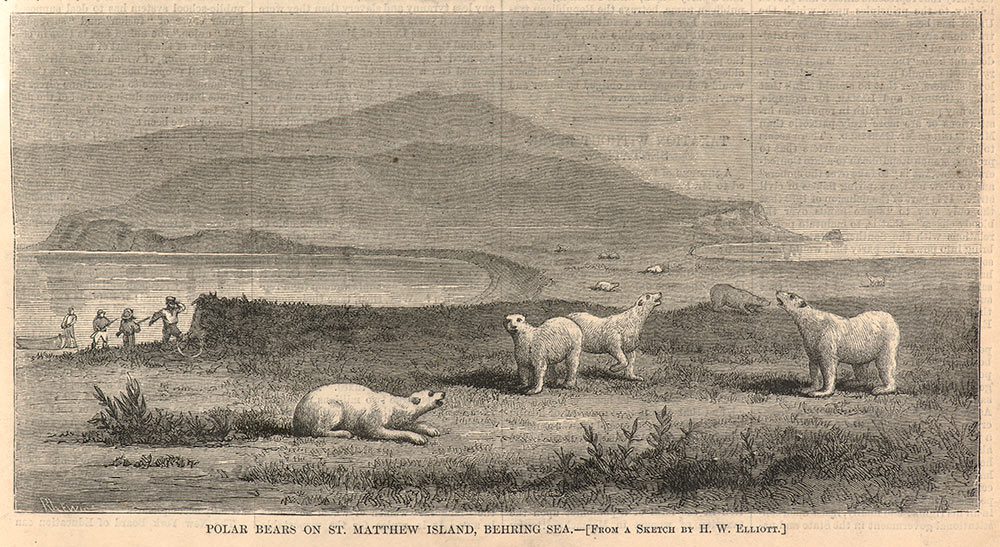

An even more iconic arctic mammal was once common here, but now is gone for good. The first whalers and sealers to venture into these waters in the 1800s often referred to St. Matthew as “Bear Island” because it was the summer home of 300 or more polar bears, probably the highest density of polar bears anywhere. These St. Matthew bears were awaiting the return of the sea ice on which they would roam through the winter. As one biologist wrote in 1874: “we landed on St. Matthew Island early on a cold gray August morning, and judge our astonishment at finding hundreds of large polar bears…lazily sleeping in grassy hollows, or digging up grass and other roots, browsing like hogs.” Many of these bears were females that had given birth to two or three cubs in dens dug into St. Matthew’s snowdrifts.

Such a notable concentration of polar bears attracted hunters, and by the Harriman Expedition of 1899 polar bears were gone from St. Matthew forever. Although old trails worn into the tundra by hundreds of generations of pacing polar bears are still visible in a few places on the island, these top arctic predators can no longer use St. Matthew as a summer home, since the winter ice pack no longer extends this far south. The inability of polar bears to recolonize this island is therefore a tragedy of our rapidly changing climate, yet for me, there was admittedly some comfort in knowing that a hungry polar bear would never suddenly appear out of the swirling fog.

I also know that we won’t come across a living reindeer as we hike among the island’s study sites, though we often encounter gray reindeer antlers with their bases firmly embedded in the tundra mosses. These are half-century-old relicts of a fleeting but environmentally transformative invasion. A Coast Guard weather station was manned here for a few years in the mid-1940s, when 29 domesticated reindeer were brought to the island to provide an emergency food source. These reindeer were released into an island environment that had been free of large grazers for thousands of years, ever since the seas rose at the end of the last ice age and flooded the shallow Bering land bridge on which St. Matthew sits. Early visitors described the island’s carpet of moss and lichen as many inches thick, far more luxuriant than on mainland sites grazed by domesticated reindeer or wild caribou. Given this carpet of rich food, the introduced reindeer multiplied exponentially, and by 1960 the herd had exploded into more than 6,000 animals. Yet they were eating food that had taken hundreds of years to grow, and with that many large grazers marooned on a small island, the lichens were quickly depleted.

A particularly harsh winter in 1963 covered the island in deep snow, and thousands of reindeer died of starvation, leaving a remnant herd of only 40 emaciated females and one stunted, permanently infertile young male. Over the next few years these last reindeer on St. Matthew also perished, yet the changes they wrought will remain for centuries. The deep mossy carpets are gone from the tundra, and expanses once dominated by reindeer lichens are now occupied by grasses and sedges.

A Welcome Newcomer

While reindeer and polar bears have not recolonized St. Matthew, some birds have done so recently, and this is good news.

Toward the end of our time on St. Matthew, Robinson returns with great excitement from a long hike to the far side of the island. As he expected, he found Black-legged Kittiwakes on his survey, one of the most abundant cliff-nesters there. But looking closely, he also saw small gulls with scarlet legs—Red-legged Kittiwakes, which were also pairing up and starting the nesting process on St. Matthew’s cliff ledges.

Red-legged Kittiwakes have never been seen breeding this far north. Instead, this range-restricted species nests only on the Pribilof Islands, and on a few of the Aleutian Islands and nearby Commander Islands of Russia. The breeding sites of Red-legged Kittiwakes in the Pribilofs have been carefully monitored for decades, and in recent years their annual breeding success has plummeted.

Robinson’s discovery that some Red-legged Kittiwakes are moving north to breed on St. Matthew suggests that they might be tracking a northward-moving food supply.

“They’ve been documented once or twice on [St. Matthew], a single bird or a pair,” he says. “Having a hundred-plus birds here along the cliff … it’s just so exciting to find something undocumented!”

This kind of natural distributional change is one way that bird species can adapt to a changing environment.

“Where Red-legged Kittiwakes traditionally breed, the sea ice does not reach those areas,” says Robinson. “The obvious difference in this year, that stands out, is that the sea ice did not reach St. Matthew Island, it was farther north.

“So I wonder if that high latitude of the winter sea ice allowed the kittiwakes to stay around the island. They had enough food and they’re here at the right time, and now they’re hanging out on the cliffs and possibly breeding.”

It’s evidence of a potentially hopeful adaptation by this seabird that’s endemic to the Bering Sea region, and facing rapidly changing conditions in its ocean waters.

And it’s one more sign that our expedition to the island is going to end in success. By our last week on St. Matthew, Andy and I have a stockpile of multimedia material—including video footage of the McKay’s Bunting’s aerial display and recordings of its song—to bring back to Cornell.

The research team has surpassed their scientific goals as well. All told, the USGS scientists have found and monitored an impressive 71 McKay’s Bunting nests and 62 Rock Sandpiper nests. Their data tell different stories about these species. For the sandpipers, which nest out in the open where they are vulnerable to jaegers and foxes, less than half of the nests made it all the way through to hatching. The bunting data, on the other hand, is heartening. By nesting deep within rocky cavities, most buntings raise their chicks in places that foxes and other predators cannot reach. Accordingly, more than 80 percent of the bunting parents successfully fledged their chicks.

Changes of all kinds are on our minds as we complete our work during these last days on St. Matthew. We have seen the snowfields slowly shrink over the course of the summer as the buntings and other birds went through their annual breeding cycle. We have appreciated the chirping of abundant voles in places where voles are naturally absent in other years, and we have heard the thunderous sound of rocky avalanches after a day of particularly heavy rain, showcasing how the island itself is a dynamic landscape. These changes are all inherent parts of the island’s environment, and they remind us that many kinds of natural change are embodied in these cycles of days, seasons, and millennia.

Meanwhile, a series of more disturbing observations has highlighted how even this most remote of islands is subject to human disturbance. Every St. Matthew beach has a detritus line of human garbage, from old netting to plastic bottles labeled in many languages. The red foxes around our camp have moved north with a changing climate caused by human activity, a warmer climate that has now made it impossible for polar bears to ever return.

Nonetheless, St. Matthew remains a spectacular wilderness, and the human footprint here is lighter than almost anywhere else I have visited. Our team was glad to find that these human-caused changes have not yet damaged the island’s unique buntings nor devastated its celebrated seabird colonies. In departing St. Matthew at the end of our work, we are proud of our accomplishments while realizing how much there still is to learn about the island and its animals.

None of us wants to leave; we all would trade the hot showers on the Tiglax for another month on St. Matthew. As the island disappears into the fog at the ship’s stern, we hope that future expeditions will find the island and its inhabitants much the way we experienced them in 2018.

Irby Lovette is the Fuller Professor of Ornithology at Cornell University and director of the Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Andy Johnson is an associate producer in the Cornell Lab’s Conservation Media program.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you