The People Behind The Birds Named For People: Alexander Wilson

By Alison Haigh, Editorial Assistant, Cornell Lab Science Communication Fund

January 8, 2018

From the Winter 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

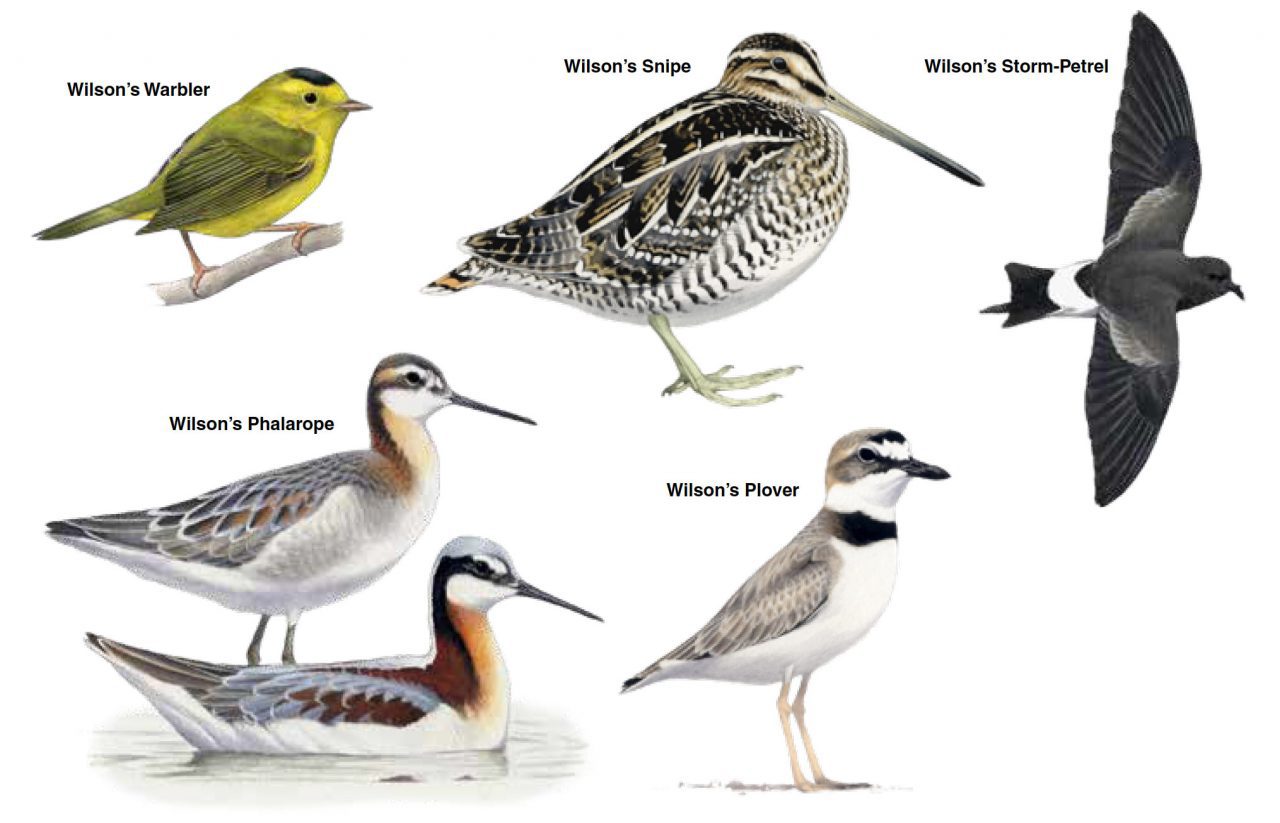

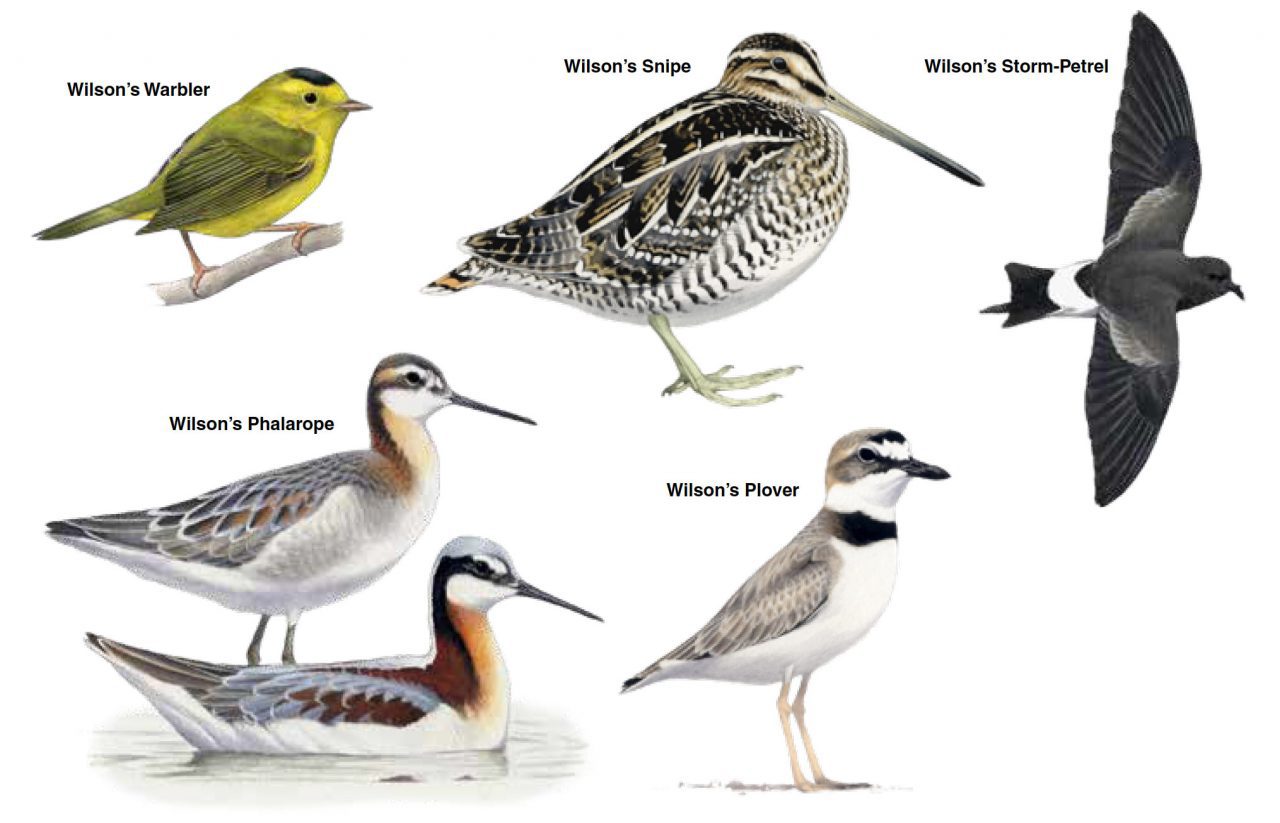

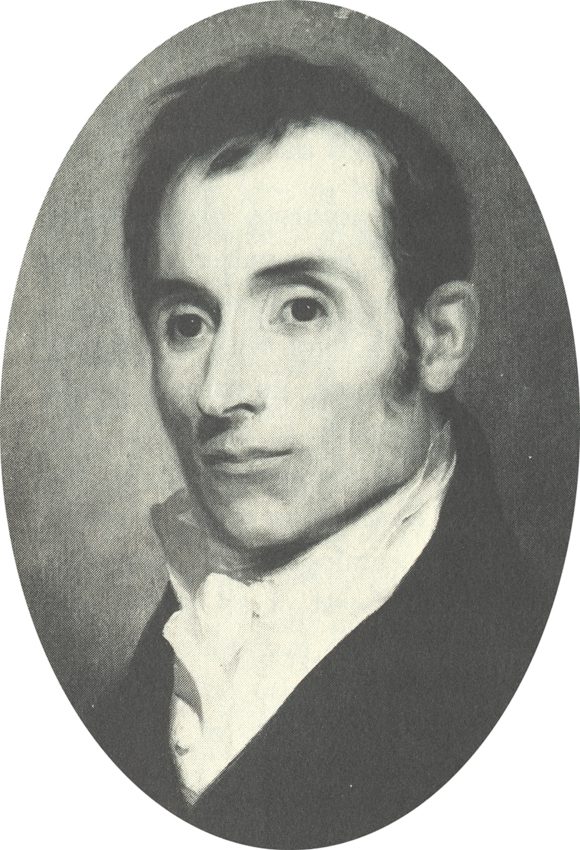

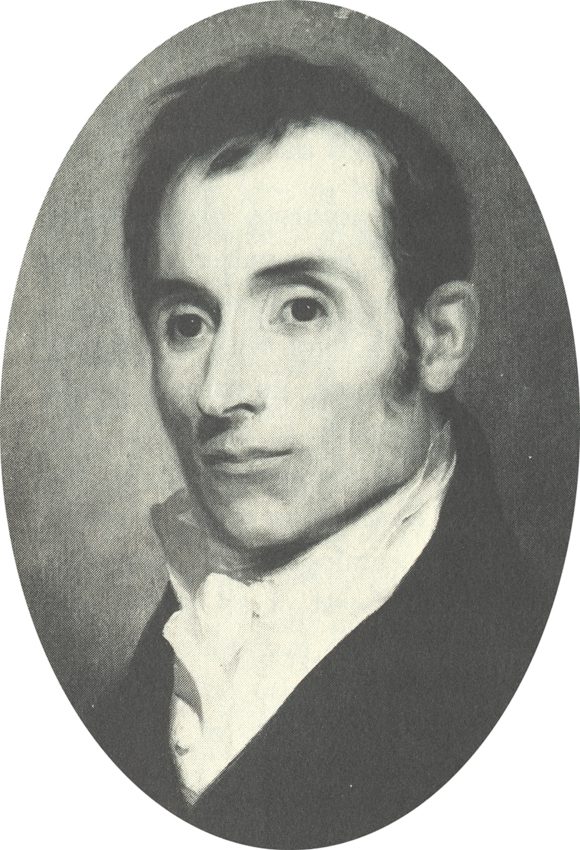

More than two centuries ago in the swamps of North Carolina, ornithologist and author Alexander Wilson squatted to sketch a yellow-green bird with a neat black cap flitting about above him, catching insects. Wilson had always favored descriptive names for birds, so he called this one the “Green Black-capt Flycatcher.” Later ornithologists changed that to “Wilson’s Warbler,” one of five North American species named for the Scottish immigrant who is widely regarded as the father of American ornithology.

That’s not just a fanciful title—Wilson actually wrote and illustrated American Ornithology, a nine-volume work published in 1814 that illustrated 268 bird species and kindled America’s insatiable appetite for bird knowledge, 30 years before Audubon’s Birds of America. Today, he has five North American birds named in his honor.

Wilson was born in Scotland in 1766. As a child, when he wasn’t gallivanting in the woods, he was burying his nose in a book or idly writing poetry. But his working-class background forced him out of school at age 13 to apprentice as a weaver. In his mid-twenties he wrote some of the industrial revolution’s first protest literature about the decrepit mill conditions he worked in. After the local government put him in jail, slapped him with court fees, and forced him to burn his work in the town square, emigration to America seemed like his best remaining option.

Wilson slept on the ship’s open deck for the four-month journey from Scotland to Delaware. Penniless and sea-beaten, he travelled to Philadelphia on borrowed money and worked odd jobs before he settled in Gray’s Ferry as a schoolteacher.

He remained restless, taking long walks through forests that twittered with birds he’d never found in Scotland. Wilson’s peregrinations took him to Niagara Falls and back, on foot, and eventually led him to William Bartram, a famous botanist who became a close mentor and friend. Bartram jogged Wilson’s interest away from poetry and into sketching, where his incredible observational skills made him a quick study—first tracing roses, then sketching simple landscapes, and eventually freehanding Bald Eagles. As an incredible artistic talent blossomed, so did an ambitious plan.

Cataloguing the birds of America had been brewing in Wilson’s mind since he settled in Gray’s Ferry. In 1806, when he left schoolteaching to start work at a prominent publishing company, Wilson approached his new boss about taking on American Ornithology. The publisher agreed, under one condition: Wilson had to procure 200 subscribers.

So, in 1808 Wilson set off on foot, “in search of birds, and subscribers.” That expedition reads like an ornithological Indiana Jones adventure. Traveling over 12,000 miles in seven years, from New England to Florida to western Tennessee, Wilson illustrated more than 230 bird species, highlighting important field marks with crisp colors, in a two-dimensional style mirrored in field guides today.

Wilson described diet, behavior, and range with poetic skill, as with the common snipe of wet fields, which he noted “have the same soaring irregular flight in the air in gloomy weather as the Snipe of Europe… [but have] sixteen feathers in the tail instead of fourteen….” (In 2003 American ornithologists agreed and split out the American form as a separate species, which they called Wilson’s Snipe.)

Off the coast of New Jersey, he spotted a swallow-sized seabird skimming the oily surface behind his boat. It’s now known as Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. All along the way, academics, officials, and bird enthusiasts jostled to see Wilson’s detailed sketches.

He sat beside a carcass for an afternoon and came away with a new bird species, writing, “Linnaeus and others have confounded this [Black] Vulture with the Turkey Buzzard.” He caught an Ivory-billed Woodpecker in North Carolina, but even after it nearly pecked through the wall of his hotel room, his biggest lamentation was that the locals thought it was a Pileated. He investigated the mysterious death of Meriwether Lewis, of Lewis and Clark. He even crossed paths with John James Audubon in Kentucky—calling him “Mr. A” in his notebook. Even though Audubon declined to subscribe, Wilson amassed 250 orders for his work by the end of his journey. He knocked on the White House door to hand-deliver his first volume to possibly his most famous customer, President Thomas Jefferson.

Many of the western birds in his book he never saw alive; he sketched the Wilson’s Phalarope from a specimen collected by Lewis and Clark. A press worker strike left Wilson to color many of the engravings himself, halfway through collecting shorebirds for his final two volumes. His work ethic and his years in the field took a toll: Wilson died of dysentery in 1813, not yet 50 years old. Wilson’s friend George Ord completed the nine-volume series, in the process naming one more species for the groundbreaking Scottish-born naturalist—a plover Wilson had found on the beaches of Cape May, New Jersey.

Alison Haigh is an Environmental Biology and Applied Ecology major at Cornell University (Class of 2019). Her work on this story was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communication Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you