Spoiler Alert: Can Gray Jays Survive Warmer Weather?

By Gustave Axelson

Gray Jay by Brett Forsyth. January 8, 2018From the Winter 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Editor’s Note: This article was published in January 2017, when the common name of this species was Gray Jay. In July 2018 the common name was officially changed to Canada Jay. Here’s more about the name change.

“Where’d they go?”

Scientist Ryan Norris was puzzled. Just moments ago, two doting Gray Jays were bouncing about the nearby spruce trees like Labrador retrievers happy to see their owner. When he wrapped a couple of cotton balls around one of the spruce tips, his rotund chums had quickly seized upon the offering. Cotton comes in handy for birds when they’re in need of insulation material for nest construction.

But Norris was playing a trick. He was using the cotton balls as a lure, and a tracking mechanism. By watching where the Gray Jays go together after they grab the cotton, he can follow them back to their nest secreted away in the black spruce backwoods. He’s been doing this for the past seven years while studying Gray Jays here in Canada’s Algonquin Provincial Park, 200 miles north of Toronto. And here he had the perfect setup: a mated male and female both eager to grab the cotton and get back to nest building.

Except that the trick was on the scientist. Each jay obligingly grabbed a cotton ball, but then they flew off in opposite directions … and disappeared.

“They’re not going to make this easy,” Norris sighed. He wore a look of not-this-again disdain, remembering past times when these jays have toyed with him on all-day games of hide-and-seek across rugged terrain and deep snow.

Gray Jays have a reputation for mischievous ways. Cree First Nations people call this bird wisakedjak, the trickster spirit of the forest. And indeed, Gray Jays are complex characters, full of paradox and irony.

They’re the people-friendly bird that loves a free handout, yet they make their homes in remote, mostly people-less forests.

They’re the bird that nests in the frozen dead of winter, and hoards food in summer when natural sustenance abounds.

They’re the warm-blooded creature that goes to great lengths to survive boreal cold blasts of minus 40 degrees, yet their future in Algonquin Park is threatened because the weather is getting mellow.

“…warmer temperatures equals spoiled food equals Gray Jay nests failing en masse.”

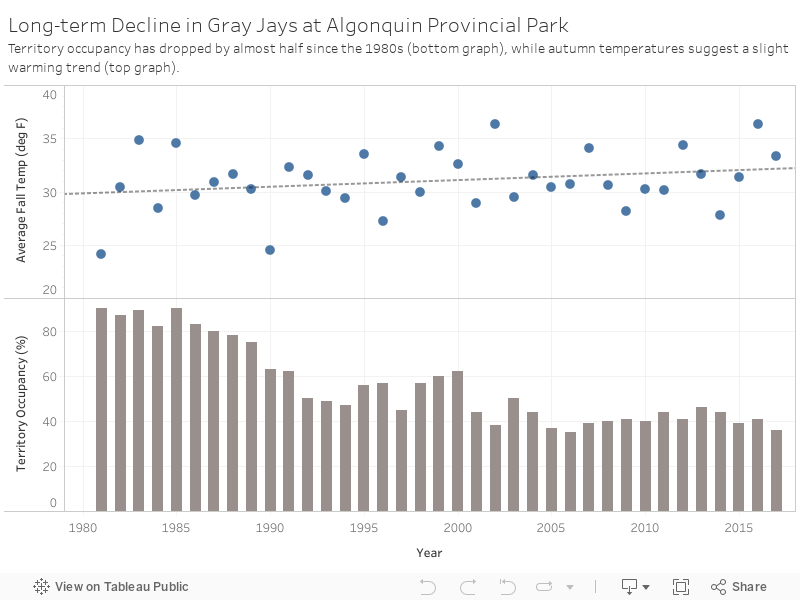

It’s that last irony—the climate change connection—that Norris, an ecology professor at Ontario’s University of Guelph, is studying. He’s the third generation of principal investigators on a research project that stretches back over a half-century in Algonquin Park. For the past 40 years, the project has documented a stark downward trend: a 50 percent decline in the study’s Gray Jay population since 1977.

The study has documented a lot of unseasonable weather in Algonquin since 1977, and this day is no exception. As Norris stood befuddled about where the Gray Jays had gone with his cotton balls, there was sweat running down his brow. It was February 23, and with blue skies and bright sun, the temperature was making a run above 10°C (50°F). Norris had already shed his winter jacket, ditched his hat and gloves, while snowshoeing out into this black spruce bog. Now he tied his hair back into a ponytail and uncomfortably tugged at his wool sweater for ventilation.

“There are not many cases of climate-change hypotheses with a direct mechanism,” he said, noting that climate-change impacts are often subtle. Insects hatch a few days earlier, the first frost comes a week or two later, and the intricate springs and gears of an ecosystem are knocked out of synchrony. But smoking guns are hard to come by. Case in point: This past autumn, scientists were reluctant to connect climate change directly to the epic hurricane season in the Atlantic, instead pointing to higher ocean temperatures and more atmospheric moisture that may have influenced storm severity in a complicated chain reaction.

In this case, however, Norris says the mechanism that’s emerging from the science appears to be as simple as warmer temperatures equals spoiled food equals Gray Jay nests failing en masse.

People-friendly tricksters that love a handout

In his 1947 species account for the Smithsonian’s Life Histories of North American Jays, Crows, and Titmice, legendary ornithologist Arthur Cleveland Bent listed more than 10 Gray Jay sobriquets, including “whiskey jack” (an Anglicized version of the Cree word) and “meat bird.” He provided the etymology for another popular nickname:

The ‘Camp Robber’ will eat anything from soap to plug tobacco. … It comes to the camper’s table at mealtime and will grab what food it can with the utmost boldness, even seizing morsels from the plates or the frying pan.

That boldness, Bent noted, has created a unique relationship between Gray Jays and humans:

It greets the camper, when he first pitches camp, with demonstrations of welcome, and shares his meals with him; it follows the trapper on his long trails through the dark and lonesome woods, where any companionship must be welcome; it may be a thief, and at times a nuisance, but its jovial company is worth more than the price of its board.

University of Guelph principal investigator Ryan Norris brings his study subjects right into the hand for Gray Jay research. Photo by Brett Forsyth.

Ryan Norris and his team of students search for Gray Jays in Algonquin. Snowshoes are required to negotiate the snowy woods. Photo by Chris Foito.

University of Guelph scientists Nikole Freeman and Alex Sutton call for a jay to land on their hands. Photo by Brett Forsyth.

Nikole Freeman on the search for a Gray Jay pair. Photo by Chris Foito.

Sutton locates a Jay. Photo by Chris Foito.

Because Gray Jays are so companionable, known to alight right on any outstretched hand to take a cracker or a piece of bread, they’re a favorite among park tourists from Algonquin to the Boundary Waters to Yellowstone to Banff to Denali. Even serious-minded scientists have a special fondness for whiskey jacks. As Alex Sutton and Nikole Freeman—two of Norris’s graduate-student researchers on the Algonquin project—snowshoed along a frozen alder creek to look for another Gray Jay nest, they sounded like they were looking for a lost pet.

Sutton stopped at regular intervals to throw his head back and let loose a long, sustained whistle. Freeman cupped her hands and called out: “Graay-aaaay. GRAAAAAY-JAAAAAAY!”

“It’s not that we’ve got them well trained. It’s just that they associate people with handouts,” said Sutton. “But it is nice to have a study subject that comes when it’s called.”

Sure enough, it wasn’t long before two charcoal-colored fluffs floated onto the scene from somewhere above the evergreen treetops. If a snowflake somehow magically transformed into a bird, it would become a Gray Jay—wafting silently, insouciantly, side to side in descent and then settling down on a spruce sprig without so much as the slightest bend of the thin branch.

Freeman set out the cotton balls, and the gentle jays immediately dropped down to grab them. Sutton watched through his binoculars

“OK, I can tell that this one is Loyal-Ooser,” Sutton said, calling out the name of the first bird to take the cotton.

These birds, like the other 60 Gray Jays being tracked in this project, have colored leg bands that allow them to be quickly identified by scientists. In the field, the researchers’ shorthand for leg-band color combinations become bird names. Loyal-Ooser is a pronunciation of LOYL-OOSR, lime over yellow left, orange over silver right.

Many of the names sound like characters straight out of a Harry Potter book, such as Rosel-Goler (ROSL-GOLR, red over silver left and green over lime right). Sometimes they sound downright derogatory, such as the teal-banded Total-Loser. (TOTL-LOSR sadly lived down to his name, never finding a mate or establishing a breeding territory in the study area.)

In this case, the female LOYL-OOSR was paired with male LOKL-LOSR, and they carried their cottony treasure in tandem up through the same opening in the spruce tops. After a bit of snowshoe bushwhacking into the forest, Freeman spied the jays threading the showy, white strands into the sticks and lichens of a nest cup 10 feet up in a spruce bough. “We have a nest!” she exclaimed.

It was one of 25 Gray Jay nests the project monitored last year. The fieldwork starts with identifying nest locations during this building phase, which begins incredibly early for a boreal bird. A female Gray Jay can begin incubating eggs as early as February in Algonquin Provincial Park, when she might be tucked in by a blanket of snow while sitting on the nest.

The project scientists return at regular intervals through March and April to check on nesting progress. Then, just before fledging, the scientists band the nestlings with colored leg bands. By April or early May, the new year’s generation of Gray Jay juveniles are out of the nest and flying through the forest—a good two weeks before most warblers have even returned from migration, much less started nesting.

“We’ll be back,” Freeman said cheerfully as she strapped on her snowshoes for the tromp back to the road.

Half a Century of Gray Jay Research

The Gray Jays of Algonquin have been studied since the 1960s, starting with research by Ontario naturalist Russ Rutter. Algonquin chief park naturalist Dan Strickland inherited the study from Rutter in 1976. By banding, tracking, and observing the park’s jays year-round, Strickland went on to become a Perisoreus canadensis pioneer—discovering much of what is known today about the species’ unique breeding biology.

Strickland was the first to document the nasty sibling-on-sibling fights that erupt when young Gray Jays are about two months old, when brothers and sisters within a brood do battle until only one dominant offspring is left. That winner gets to stay with father and mother on their natal territory throughout the winter and into the next spring, whereas the subordinate siblings are exiled into the wild.

In 2009 Ryan Norris and his program—the Norris Lab at Guelph’s Department of Integrative Biology—joined Strickland on the study. Now retired, the 75-year-old Strickland still works with Norris during the winter field research season in Algonquin. When the two scientists—the emeritus and the current principal investigator—drive into the park from its western gate, the old-timer points out all the spots where Gray Jays used to be.

“It’s like a driving history lesson,” Norris says. “He [Strickland] will say, ‘Back in the 1980s, there were jays here, and here, and here. But geez, nowadays there haven’t been Gray Jays there for years.’”

It was Strickland who taught Norris the cotton-ball trick for locating Gray Jay nests. But Norris wasn’t having much luck with it on this winter day. At another breeding territory, two jays showed up to take bits of bread from his sandwich, but they ignored the cotton.

“I don’t know if it’s the warm weather or what, but they’re not interested in nesting right now,” he said. “They just want to eat.”

One of the jays flew off across the road with a bread scrap, and Norris followed on snowshoes, curious to see where it was headed. The snow was more than 2 feet deep, typical for an Algonquin winter, but it was beginning to rot out from underneath. On one step, Norris’s oversized metal feet punched through and he sunk up to his thigh. The air had a dewy feel—damp and clingy. Dark gray clouds huddled up in the sky.

Norris caught a glimpse of the Gray Jay in a scrawny black spruce on the edge of a bog. When he drew closer, the bird flew off, but Norris spied a little brownish-yellow nugget wedged into the flaky bark of the spruce. Upon closer observation, the nugget turned out to be an old peanut with a bit of white goo on it. Norris had discovered a Gray Jay cache.

Gray Jays hide little caches of food throughout their territories in late summer and autumn, so they’ll have a ready larder for winter. Whereas chickadees scrap and scuffle for any tidbit of protein they can glean when the snow is deep and the temps subzero, Gray Jays take it easy, making leisurely trips to a stocked pantry of mushrooms, nuts, berries, and venison they have stashed all over the woods. Evolution even gave Gray Jays extra-large mandibular glands that produce a specialized sticky saliva for rolling bits of food into gooey packages, called boli, that can be crammed into the nooks and crannies of tree bark, kind of like kids sticking gum under a desk. It’s the perfect survival strategy for a cruel boreal winter.

To pull off this feat, Gray Jays possess incredible cognitive recall abilities (it’s a corvid family trait, shared by Pinyon Jays and Clark’s Nutcrackers). For Gray Jays, accessing their clandestine food depository is like playing the world’s biggest game of memory. They can hide up to 1,000 little food packages per day, upwards of 100,000 in a season. And they must remember where all those caches are stashed across a nesting territory of 140 hectares, or more than 250 football fields of dense forest.

It’s this immense stashed food supply that allows Gray Jays to begin the energy-extravagant act of nesting in the middle of a lean northern winter, when kinglets are huddled up inside a tree cavity trying to stay warm. Caching may also explain why Gray Jays nest so early, according to Strickland. He posits that the early start makes it possible for young to be off the nest in May, so they have a longer summer to develop cognitive skills and learn how to construct an extensive hidden food network. In other words, early nesting allows for a kind of Gray Jay head-start program.

It’s an ingenious strategy, stocking away food in freezer storage so that it lasts all winter. But it may have one fatal flaw: As Norris puts it, “What if somebody leaves the freezer door open?”

Unlike other caching birds such as nuthatches, which store away nuts and seeds as supplementary food sources in a pinch, Gray Jays rely on caches of perishable foods—berries, mushrooms, meat—for a successful breeding season. In 2006, Strickland published a paper that correlated unseasonably warm autumn weather in Algonquin with lower Gray Jay reproductive success the following spring. Strickland suggested that the warm weather was causing the Gray Jays’ food to spoil. He called his hypothesis “hoard rot.”

When the leaden clouds above started to spit drops of rain, Norris sighed with exasperation and followed his snowshoe footprints back to the road. He looked over his shoulder to see that same Gray Jay return and dislodge the peanut from its hiding place, then fly over to another spruce tree. There are plenty of thieves in the woods, and if a Gray Jay’s cache location is compromise—whether by Blue Jay or human—the cache will be restashed immediately.

Back in his car, Norris called it a day and drove home, passing a little local hockey rink that was morphing into a reflecting pool. A sign attached to the goalie net read: “ICE RINK CLOSED DUE TO MILD WEATHER.”

Overhead, lightning flashed and the sky rumbled. A thunderstorm was rolling into Algonquin Provincial Park. In February.

Abandoned Nests: Climate Impacts Food Availability

By midafternoon in Algonquin, Gray Jay nestlings are getting restless, ready to fledge. It was time for more nest checks.

On a bright early-spring day, Nikole Freeman set off from a dirt back road to visit the first nest on her route. Grassy stubble was emerging by the road’s edge, but the snow was hip deep back in the woods. She donned snowshoes and trudged farther, only to encounter knee-deep meltwater ponds that had submerged the bases of the spruce trees, creating a kind of boreal bayou. Such is spring in Algonquin.

Freeman carried on and finally reached a black spruce tree festooned with orange plastic flagging at the back edge of this Gray Jay pair’s territory. This was the nest tree, but as Freeman glassed upwards about 20 feet, the nest was empty.

“Maybe the female’s out foraging,” Freeman reasoned. Then the male, ROSL-GOPR, arrived and started picking at the ends of branches near the top of the tree. He snapped off a twig by seizing the branch tip with his bill and flapping his wings to lift off. This was not a good sign.

“That behavior means he’s collecting twigs to build a nest, a new nest,” Freeman explained. “That means this nest has failed.”

ROSL-GOPR and his mate had already lost their first nest back in early March. Now this, and yet they appeared to be making a third attempt very late in the season, when the chances of nest failure for Gray Jays are highest.

Failed nests are becoming more and more common in this study. Often the cause is abandonment. During the prior spring, Norris and his graduate-student crew found several nests occupied by dead nestlings. The Gray Jay parents were still present on the territory, though, even meeting the scientists at the nest.

“It’s like they just stopped feeding their young,” Norris says. “That points to a problem with food availability.”

Norris has found a strong correlation between high rates of nest success—or failure—and the weather. The winter of 2014–15 was bitterly cold in Algonquin Park, and that spring the Gray Jays enjoyed their highest reproductive output ever in the study’s 50-plus years. A record number of pairs produced clutches of four offspring (Gray Jay clutches are typically two or three), and nestling survival was 100 percent across the study, which included more than 20 nests. Sixty-nine young jays were added to the local population, a recruitment rate up 50 percent over the long-term average.

The next winter of 2015–16 stalled out. Due to a “crazy warm autumn,” according to Sutton, the ice-in date in Algonquin (the day that lakes freeze over) wasn’t until January, the latest ever in the park’s recorded weather history. Throughout that winter snow cover was sparse and patchy, with several weirdly warm days when snow would melt during the day and refreeze at night.

That following spring was when Norris found several nestlings starved to death. At the end of the breeding season, the nest failure rate was nearly 50 percent—the highest failure rate in the history of the Algonquin Gray Jay study.

Several recent years have been full of similar correlations. In 2015 researcher Talia Sechley, working with the Norris Lab, published a scientific paper in the Canadian Journal of Zoology that posited fall and winter temperatures in Algonquin were no longer getting low enough to properly freeze the food caches of Gray Jays and stave off decomposition (or in Strickland’s parlance, hoard rot).

To zero in on causation—the exact climate mechanism at work here—Sechley and research partners explored just how hoard rot might work by planting simulated Gray Jay caches (little plastic boxes filled with mealworms and raisins) in Algonquin Park and at a site 300 miles farther north near Cochrane, Ontario. Caches were planted in September and retrieved in March. At Cochrane, temperatures rarely went above freezing beyond October, whereas Algonquin temperatures dipped above and below the freeze point.

Anyone who’s tried to cook up a steak that’s been defrosted and refrozen knows what happened to the Algonquin caches: freezer burn. At the end of the experiment, the caches in Algonquin had 50 percent less nutritional value than the Cochrane caches.

Through further analysis of the region’s weather history, the Norris Lab found that the climate in Cochrane today closely resembles the climate that used to be in Algonquin in the early 1990s. But temperatures in the park have been trending above the long-term average over the last two-and-a-half decades—the same time period of a hard dive in the local Gray Jay population.

Sutton sums all this research up in four words: “Climate impacts cached food.”

Even the Beyoncé of Gray Jays Struggles With Hoard Rot

Freeman yearned for better news at the next nest check. At a hiking trailhead, she rejoined Norris, who was fresh back from scouting out a potential Gray Jay research project in Alaska. He had been to Minnesota the month before. As the evidence of decline in Algonquin piles up, scientists elsewhere are eager to look into what’s happening with Gray Jays.

Should the Gray Jay become the national bird of Canada?

There are still about 26 million Gray Jays from coast to coast across the boreal and alpine biomes of northern North America, in every Canadian province and 14 U.S. states. So the species is far from endangered. But Breeding Bird Survey data portray regional declines, especially along the southern periphery of the Gray Jay range from the Maritime Provinces to the Rocky Mountains. BBS data depict an overall 19 percent decline in the continental Gray Jay population since 1970. That decline is even more pronounced in the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Project FeederWatch, in which the proportion of backyard bird feeder sites reporting even just one Gray Jay has dropped by 50 percent since 1999.

But the team—Norris, Freeman, and Sutton—had reason to be upbeat at the next nest, because they were entering the realm of YOSL-BOBR, dubbed the “Beyoncé of Gray Jays” by researchers on the project.

“It’s hard to describe the aura of Yossel-Bobber,” explains Sutton. She’s always the first to arrive when humans are in her neck of the woods. She’s not afraid to get right up in a person’s face. And she’s alpha-dominant, which has made YOSL-BOBR an avian model of female empowerment among women researchers in the study. Even though Gray Jays are known to choose mates for life, YOSL-BOBR is on her third mate—having decided the previous two males weren’t up to snuff.

True to form, YOSL-BOBR charged out of her nest tree at the sight of Freeman and dropped right to the scientist’s wrist to take a piece of Wonder Bread. When her mate OOBL-KOSR came to get some, YOSL-BOBR bumped him out of the way and grabbed a second bite.

“The differences in personalities among Gray Jays are striking, and personality permeates everything they do,” said Norris. He admits that all birds have personalities, but, he says, “with Gray Jays it’s very evident because they come right to your hand. A warbler won’t do that.”

Norris says that within the variation among Gray Jays, there are some personalities that may relate to successful survival and reproduction. One of his lab’s studies showed that the most outgoing, people-friendly Gray Jays benefited during the breeding season. Graduate student Rachel Derbyshire analyzed the long-term project data and found that Gray Jay pairs that regularly visited park tourists for food tended to lay their eggs earlier and have larger clutches and broods than birds that didn’t seek out people for handouts.

For Gray Jay nest checks in Algonquin, scientists climb ladders braced against skinny spruce trees just a few inches in diameter. Photos by Chris Foito.

A nest of Gray Jay chicks (top). Chicks are examined to check for health.

Optimistically, this research could be a sign that Gray Jays possess what scientists call behavioral plasticity, or flexibility—the capacity to roll with the punches, innovate new solutions, and take advantage when opportunities arise. And this may be true for some individual Gray Jays. But the research didn’t show that feeding Gray Jays is the way to save them as a population.

“Obviously, food supplementation is not enough of a benefit to offset the overall trend along Highway 60,” says Norris. Even along Algonquin’s prime tourist corridor, Gray Jays are still in long-term decline due to a lack of recruitment, or adding new birds to the population.

With YOSL-BOBR occupied by grabbing food from Freeman’s hand, Sutton set up a painter’s ladder against a skinny black spruce nest tree, climbed 15 feet high, and peeked into YOSL-BOBR’s nest.

“Only one,” he called down.

Norris quickly tallied up the results of his team’s nest checks on this day—one failure, two nests with one nestling, and one with two nestlings. With two adults for each nest, that’s a total of eight adults and four nestlings.

“Not even a rate of replacement,” Norris said.

Norris weighs Gray Jay chicks as part of assessing their health. Photos by Chris Foito.

Chicks are looked over and their health is assessed by the team. Before they are placed back in the nest, bands are attached to their legs.

Sutton and Freeman worked quickly on YOSL-BOBR’s single young, a plump little one almost fully feathered in slaty-gray juvenal plumage. Freeman kept it warm inside her woolen winter hat while Sutton measured it with calipers and a mini-spring scale. Within five minutes Sutton was back atop the ladder, depositing the newly dubbed GOSL-WOGR—with fresh green, silver, and white leg bands—back in the nest.

Ten days later, GOSL-WOGR would fledge and fly off with YOSL-BOBR and the father to begin a year’s apprenticeship in the family trade of caching food.

But across the Algonquin Gray Jay population, many nests had disappointing outcomes. The 2016–17 breeding season saw another 50 percent nest failure rate, the second in a row. Whereas the prior lackluster season had an unseasonably warm autumn, this breeding season had been broken up by a strange mid-February thaw punctuated by a thunderstorm.

“It’s further evidence of hoard rot, that unseasonable warm temperatures disrupt the breeding strategy of Gray Jays,” says Sutton. “Each year’s research is like adding another puzzle piece, and the picture becomes clearer.”

Radio Tags Lead to Stands of Black Spruce

By late August, Gray Jays become different birds.

“What can be the friendliest bird in the world to you in winter, doesn’t care a lick about you in summer,” Sutton said. He was holding a metal-pronged radio antenna, the device he now had to use to find Gray Jays. During this summer lull after the breeding season, but before a new caching season, the jays don’t find much use for people and their handouts. “If you happen to cross paths with a Gray Jay, they might take your food,” Sutton said. “Might.”

So for year-round tracking, some of the jay fledglings are outfitted with radio tags as well as leg bands. Sutton was following the intermittent sounds—tick, tick … tick—of a radio tag attached to a juvenile Gray Jay male named WOPL-OOSR, and the sounds were leading him straight into black spruce.

Black spruce is the tree that is inextricably linked to wherever Gray Jays still exist in Algonquin. The flaky bark provides an excellent medium for hiding caches. Norris’s research on simulated Gray Jay caches also showed less spoilage in black spruce, perhaps because the tree’s resin possesses microbial preservative qualities. Other studies have shown that an entire stand of black spruce can provide a cooler microclimate for boreal wildlife such as moose.

Whatever the reasons, Algonquin’s Gray Jay population has entirely receded out of deciduous maple tree cover (the now-empty places of Strickland’s remembrances). Every jay breeding territory today contains a significant black spruce component. If there is good news, it’s that black spruce is still common on the landscape, and Norris says the long-term Gray Jay decline seems to have leveled out recently, with the population stabilizing at a lower level.

Still, the scientists are worried about the past two consecutive years of breeding failures. A downward turn among the Gray Jays in black spruce territories could signal the species’ final chapter in Algonquin Park.

Sutton was worried about what WOPL-OOSR’s radio tag was telling him. The ticking appeared to be emanating from the ground. Sutton had the metal antenna pointed at a mossy hummock on the forest floor, and the ticks followed in rapid succession.

“Hmmm,” puzzled Sutton. Internally, he was having a gruesome flashback. Twice before he had picked through the sphagnum moss to retrieve a radio tag. Once he found a headless Gray Jay, the other time he found a head but no body—pine marten victims, he guessed.

This time, as he dug through the moss, a soft whistle sounded overhead. Sutton looked up to see WOPL-OOSR, balancing on the single tine of a spruce treetop, smartly dressed in his adult plumage with a gray-feathered jacket and a partial dark cap like a black bowler tilted back on his head.

The bird had been so close to Sutton, its radio tag signals bounced off the ground and reflected back to his antenna.

The scientist just smiled. Trickster of the forest, the Gray Jay is full of surprises.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you