From the Winter 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

If loud, anxious chattering from high above interrupts your peaceful walk in the woods this winter… look up! You might be thrilled to catch a roving flock of Red Crossbills ravenously extracting every last seed from the cones at the top of an evergreen tree. These plump finches are famous for their extraordinary bills with a sickle-like top mandible that crosses the bottom like a pair of busted scissors.

Thanks in part to the drought of 2016 and wet spring of 2017, this winter the spruces, hemlocks, pines, and other conifer trees across parts of the Midwest and Northeast are bursting with the biggest cone crop in decades. At the same time, conifer crops across the mountainous West and much of the western boreal forest—the typical winter haunts for most crossbills—are failing. According to Matt Young, who works for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library and has studied Red Crossbills for the past 20 years, the conditions are brewing for a major irruption of Red Crossbills this winter. “Red Crossbills are on the move,” says Young, “and this year’s movement is shaping up to be the most impressive in recent history.”

The Crossbills are Coming

In North America, Red Crossbills occur in coniferous forests from Alaska to eastern Canada and the northeastern United States, with the biggest populations concentrated in the coastal and mountain forests of the Pacific Northwest and the Rockies. Unlike most birds in temperate areas, Red Crossbills have two breeding seasons in a calendar year. The first is in late summer, right when cone crops are ripening. The second breeding cycle comes after cones have matured. From winter through spring, crossbill flocks from a dozen to several hundred birds roam the landscape looking for a food supply of evergreen cones that can support a second round of nesting.

And when the cone crops fail in the West, hordes of hungry crossbills come east looking for food.

The last major Red Crossbill irruption was during the winter of 2012–13. During that cycle, crossbills started showing up in Kansas in July, and by August they were spreading across the Great Lakes states and Ontario into the Northeast. Come January and February, Red Crossbills moved south into Massachusetts and New Jersey, and by winter’s end there were crossbills reported in Kentucky, Oklahoma, even Arkansas.

Based on early observations, this winter is shaping up to be even more spectacular. Observers in the upper Midwest saw an unusually large number of crossbills this past summer, says Young. eBird data indicate that in June and July, large numbers of Red Crossbills were moving down the West Coast as far as Southern California. As summer progressed, reports poured in from Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan as the wave of Red Crossbills spread eastward. An observer at Stony Point near Duluth, Minnesota, counted nearly 1,100 Red Crossbills moving south along the shore of Lake Superior in late October, an all-time high count for the state according to eBird.

Red Crossbill numbers were also well above average in Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, and northern New York, where evergreen forests typically host a modest breeding population in summer.

Photo by Ryan Schain/Macaulay Library.

More Than One Type of Crossbill

The Red Crossbill species in North America consists of 10 types, each with a distinct bill size and shape that’s best suited to certain conifer species. While some crossbills have small bills perfect for cracking into tiny hemlock cones, other crossbills have bigger mandibles that can pry open ponderosa pine cones. This year many of the crossbills’ favorite cones are on the buffet across the Great Lakes and Northeast.

“The spruce cone crop in the eastern U.S. this year is the best in at least a couple of decades, and it’s coinciding with a better-than-average cone crop on hemlock, white and red pine, and even tamarack,” says Young. “It is rare to see soft-coned conifers such as spruce and hemlocks produce great cone crops in the same year as hard-coned red pine. And all crossbills love the white spruce. It’s the universal crossbill munchy!”

Put it all together, and Young says, “It’s a ‘perfect storm’ of crossbill food.”

Each type of Red Crossbill also has its own distinct flight call (known by numeric call types, such as “type 1,” “type 2,” etc.). Young’s research for the Macaulay Library focuses on the various crossbill call types. He says this winter has the exciting potential for multiple call types to converge in the Midwest and East—some of which are rarely seen, or heard, outside of the western U.S.

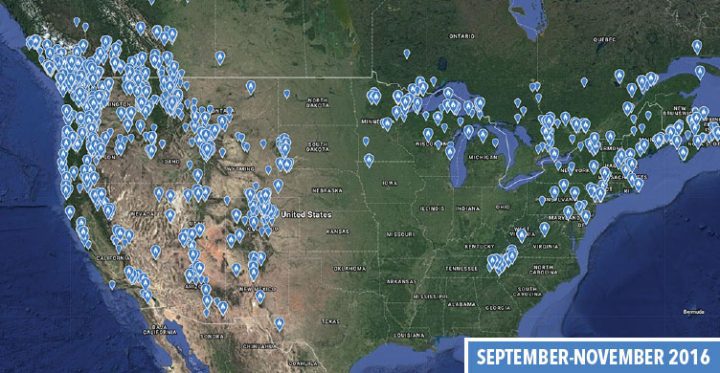

Red Crossbill sightings in autumn 2016 show their typical distribution, mostly in the mountainous West with pockets in conifer forests in the Upper Midwest and eastern mountains. View map at eBird.

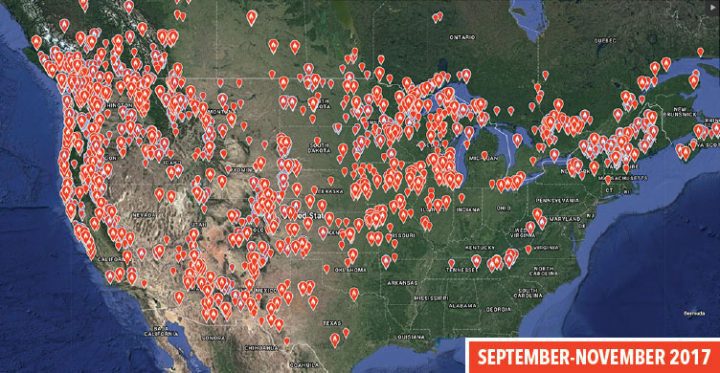

eBird data depict 2017's Red Crossbill irruption in action. This autumn, waves of Red Crossbills filled in the Plains states and blanketed two-thirds of the Lower 48 states. View map at eBird. Maps provided by eBird.

Young encourages birders to submit sound recordings of crossbills with their eBird checklists this winter, in order to help scientists sort out which crossbill call types end up where.

“Even using the voice memo feature on your smartphone can get a decent recording that can help to identify a crossbill type,” he says. “Just open your audio recording app, hit record, hold your phone as steadily as possible facing the crossbill, and then add the recording to your eBird list.”

What’s more, the cone crop bonanza could yield more than just Red Crossbills. Ron Pittaway’s Winter Finch Forecast—the Old Farmer’s Almanac of finch irruption predictions, produced by the founding member of the Ontario Field Ornithologists—foretold of White-winged Crossbills, Pine Siskins, and maybe even redpolls spreading into the northeastern U.S. this winter.

According to Young, various finches will be spreading out across North America in coming months.

“Common Redpolls are already in the Rockies, Pine Siskins have been spotted along the Gulf Coast, and Cassin’s Finches are appearing in desert lowlands of the West in numbers not seen in years,” he says.

And because of that second breeding cycle for Red Crossbills, Young says the irruption may not end when the snow melts.

“This event should carry on right into the spring,” he says. “Crossbills should be breeding in many areas between January and April.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you