Lost Birds: The Search to Rediscover Species That Might Not Yet Be Extinct

By Sarah Gilman

Blue-eyed Ground-Dove by Rafael Bessa. June 8, 2017From the Summer 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The song was a surprise: A succession of coos like water drops, both monotonous and musical. They sounded sleepy, familiar, and yet just foreign enough to catch ornithologist Rafael Bessa’s attention.

It was a brilliant June afternoon in 2015, and the song fluted from some rock outcroppings near the verdant palms of a vereda, or oasis, in an expanse of shrubby grasslands in southern Brazil. The country’s Amazon rainforest has long captured conservation headlines, but the cerrado—as this mixed savanna of grass, brush, and dry forest is called—covers 20 percent of the country’s landmass, and is more threatened. Bessa himself was there in the state of Minas Gerais to conduct an environmental assessment for a proposed agricultural operation. He had stumbled on the vereda while driving from his hotel to a distant survey site. There was no time to investigate the plaintive call, but the “woo-up…woo-up…woo-up” sounded a bit faster and deeper than the Ruddy Ground-Doves that occur in abundance in the area. Bessa decided to return.

The next day, he managed to record the mysterious call and summon its maker into a nearby bush with the playback. He aimed his camera and took a series of photographs, then zoomed in on the images.

It was indeed a small dove—not necessarily the sort of quarry birders get twisted up over. Its back was an unspectacular greenish-brown, and its head, tail, and breast were a muted ruddy orange, blending to a creamy belly and a set of bony pink feet. But its eyes were arresting pools of spectacular cobalt blue, echoed by little half moons of the same dabbed across its wings.

Bessa’s hands began to shake. “I had no doubt that I found something really special,” he says.

Seeking confirmation, he texted his friend Luciano Lima, the technical coordinator at the Observatório de Aves of the Instituto Butantan, São Paulo’s biological and health research center. Lima had done his master’s degree in a museum with an extensive specimen collection, and agreed to drive to his office to pull up the photos on his computer and see if he could identify the mystery dove.

“I was in my car,” Lima recalls, “and he suddenly sent me one of the pictures, and I almost crashed!”

Lima called Bessa back from the institute: “‘Hey man, you found the bird! You found the bird!’ I remember repeating it to him like a thousand times.”

Bessa had discovered a pocket refuge of Columbina cyanopis, the Blue-eyed Ground-Dove. The creature was exceedingly rare; some suspected it was extinct. Though there had been a few published sightings over the past couple of decades, it hadn’t been documented with hard evidence in 74 years. And Bessa had taken the first-ever photos and recordings of the bird some 600 miles away from the nearest place specimens had been collected.

“There is thousands and thousands, and hundreds of thousands, and millions of thousands of hectares, and he just managed to be in the exactly right place,” Lima marvels.

When Lima himself went out to see the bird a year later, after the rediscovery was announced, he was overcome.

“I don’t have words to describe it,” he says. “It’s like seeing a ghost.”

Lazarus Species

The reappearance of such ghost species isn’t as unusual as you might think. According to a 2011 review in the journal PLOS ONE, some 144 bird species have been “rediscovered” over the last 122 years, the vast majority of them after 1980. In 1984, ornithologist Dick Watling stumbled on the “extinct” Fiji Petrel after years of searching when a juvenile flew into his head one rainy night.

“A more undignified return to human awareness after 129 years of peaceful oblivion could not be imagined,” Watling later wrote.

In a recent wave of finds, researchers turned up the Banggai Crow, not seen since 1900, in Indonesia in 2007; the Jerdon’s Babbler, undocumented since 1941, in Myanmar in 2014; and, the Blue-bearded Helmetcrest hummingbird in Colombia in 2015, after a 70-year absence.

Against the backdrop of a human-caused sixth mass extinction, it’s tempting to regard such tales as glimmers of light in a dark time. Just as there is a recently coined term for the last individual of a species—an endling—so too is there a much older phrase for those that reemerge—a Lazarus taxon, named after the man Jesus brings back from the dead in the Bible.

Still, rediscoveries say less about miraculous recovery than they do about our limited knowledge of a world we are reshaping at a breakneck pace. As Paul Donald, Nigel Collar, Stuart Marsden, and Deborah Pain wrote in their 2013 book, Facing Extinction, nearly all birds “begin their taxonomic lives—their epistemological existences—as rarities,” known only from one location and a specimen or two. It’s only with consistent attention and study that a more complete picture of a species emerges—where it lives, what it needs, how numerous it is. Even today, though birds are some of the best-studied creatures on Earth, many species remain “inveterate skulkers in the historical undergrowth.”

More On Birds Coming Back From the Brink

The 2011 PLOS review found that 40 percent of rediscovered bird species were known only from the original type specimens that led to the first formal description of the species, decades to centuries ago. Some may have been hard to refind because their collector hadn’t noted basic details about the location of capture, let alone life history and habitat requirements. Others may not have been resurveyed or confirmed because they were remote and had secretive habits that made them difficult to track. Or people simply may have not been searching for them. Some were locked away in conflict zones where it was dangerous to search. For example, the Táchira Antpitta—a leggy, quail-sized bird known only from four specimens collected 60 years ago—has been difficult to reconfirm because it was initially found in cloud forests on the Venezuela-Colombia border, an area rife with guerrilla activity and drug trafficking. [Note: the Táchira Antpitta has since been rediscovered by a team led by Venezuelan biologist Jhonathan Miranda, announced in July 2017.]

As the number of searchers and searches has increased—with more taxonomists, bird watchers, ecotourists, and expeditions—so too has the number of rediscoveries climbed, particularly in the tropics where there are vastly more species. Ironically, increasing incursion into and development of wild places has probably also fed the trend.

“If a bird has not been seen in North America or Europe for several decades, then it’s a safe bet that it just isn’t around anymore. Too many people looking, too few places to hide,” explains Neotropical bird expert Tom Schulenberg, a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. But “countries in the tropics tend to have less in the way of infrastructure. Fewer roads, fewer scientific institutions, fewer biologists, less money to throw around on pursuits such as searching for lost species.” That leaves more yet to discover—and rediscover.

If a “lost” bird species has made it long enough to be rediscovered, there is the hope of helping them eke out an existence for a little longer.~Tom Schulenberg

For hard-to-find creatures, the difference between steep population decline and actual extinction is a murky one. Often rediscoveries simply reveal that a rare species is getting rarer. Some 86 percent of birds described in the PLOS paper remained highly threatened when they reappeared on the scientific radar, many for decades afterward.

Still, reemergence is also evidence of resilience, and a chance at some kind of redemption. A small population makes a species more vulnerable to random destructive events and inbreeding, but it’s not necessarily a death sentence. Biologists have successfully used interventions such as nest protection and captive breeding to bring California Condors back from 22 individuals in 1981 to more than 200 in the wild in 2014, and Mauritius Kestrels from the last four of their kind in 1974 to a wild population of around 400 in 2012.

If a “lost” bird species has made it long enough to be rediscovered, Schulenberg says, “there is the hope of helping them eke out an existence for a little longer.”

Hunting for Ghosts

That hope is what Daniel Lebbin, vice president of international programs at the American Bird Conservancy, had in mind when he cooked up the organization’s Lost Birds of the Americas project about three years ago. Combing over the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, Lebbin made note of some 24 birds that were listed as critically endangered, but hadn’t been seen in the wild for a long time. Then, he eliminated some species that had already been searched for unsuccessfully, and island endemics that had likely been devoured out of existence by invasive species such as rats or killed off by exotic disease. In the end, he was left with just a few continental species whose potentially larger ranges left more room for holdouts.

Chestnut-bellied Flowerpiercer Last Seen: 1965 — Found: 2003 A small tanager found at higher elevations in a few locales in Colombia. Flowerpiercers feed on nectar by piercing the bases of flowers. Photo by Ciro Albano.

Dusky StarfrontletLast Seen: 1951 — Found: 2004 Deforestation and mineral extraction threaten the incredibly small range of this bird in northwestern Colombia. Photo by Nigel Voaden/Macaulay Library.

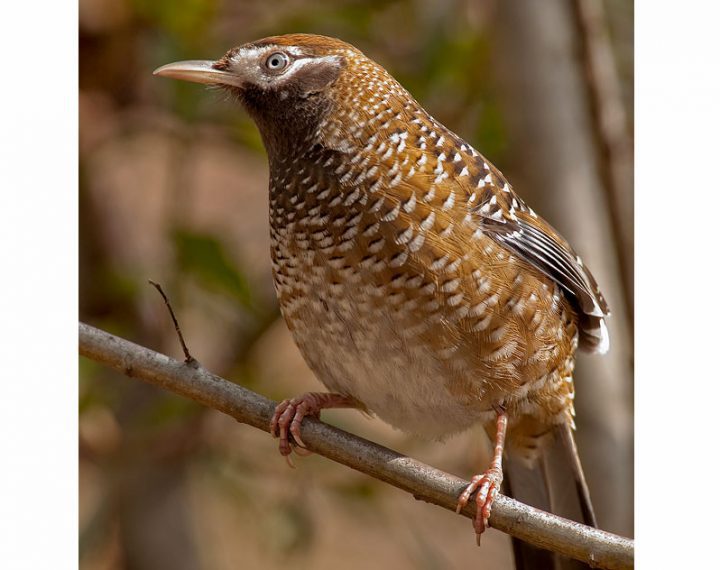

Biet's LaughingthrushLast Seen: 1989 – Found: 2008 Scattered populations in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces in China are small and declining due to habitat loss. Photo by Alister Benn.

Rusty-throated Wren-BabblerLast Seen: 1947 - Found: 2004 A tiny, vocal songbird in the Mishmi Hills in northeast India. Photo by Claudio Koller.

Kaempfer's WoodpeckerLast Seen: 1926 — Found: 2006 A bamboo specialist with populations that are uncommon despite its broad range in eastern Brazil. Photo by Ciro Albano.

Recurve-billed BushbirdLast Seen: 1965 — Found: 2004 A remarkable-looking antbird from Venezuela with a bizarrely large, wedge-shaped and upturned bill. Photo by Chris Sharpe.

Cone-billed TanagerLast Seen: 1938 — Found: 2003 Currently known only from two sites in central Brazil, but additional populations may be discovered as more fieldwork is conducted. Photo by Bertrando Campos.

Yellow-eared Parrot Last Seen: 1919 – Found: 2005Large, nomadic species that nests in wax palms in western Colombia and possibly northern Ecuador. Photo by Felix Uribe.

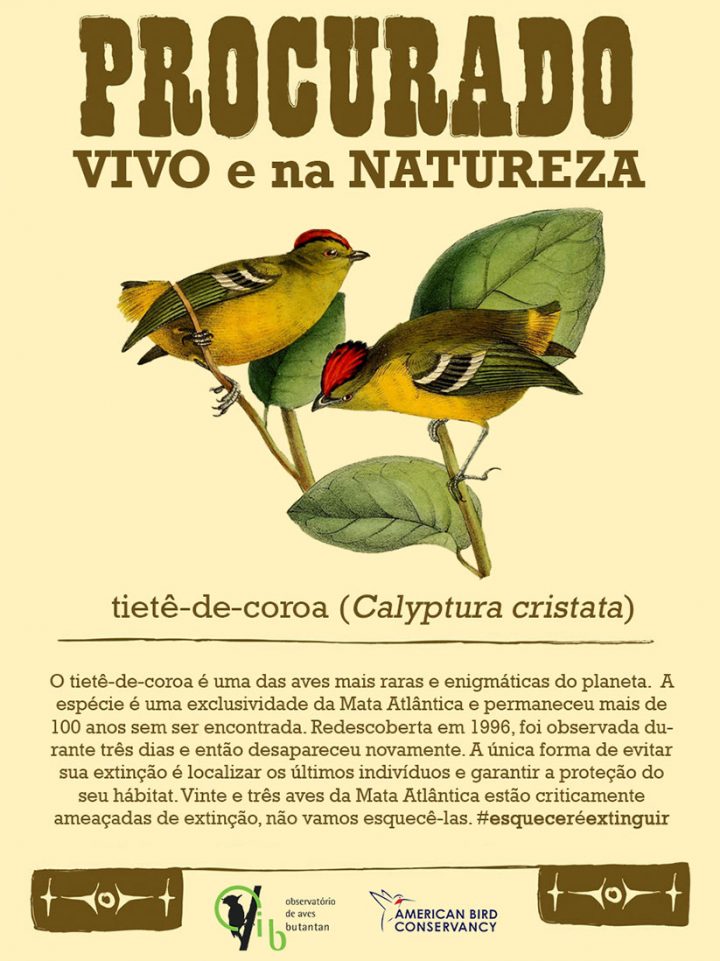

There was the Turquoise-throated Puffleg—an Ecuadorian hummingbird with colors as flamboyant as its name, collected in 1850, with an unconfirmed sighting in 1976. There was Brazil’s Kinglet Calyptura, which had vanished for 119 years before a brief dip back into scientific consciousness in 1996. And there was the Táchira Antpitta, the enigmatic species that had vanished into a zone of guerrilla conflict that now seems to have quieted a bit.

“Not much is going to happen conservation-wise for these birds unless you know where they are,” Lebbin says. And with habitat destruction proceeding apace, not looking for them raises the prospect of what some biologists have called the Romeo Error: In Shakespeare’s classic play, Romeo ensures Juliet’s death by believing, wrongly, that she is already dead.

Lost Birds expeditions have been carried out and are continuing by South American partner organizations with ABC’s funding, but none have yet resulted in published, peer-reviewed finds. And even if they do, more study will likely be needed to help the birds.

“If we don’t know how many, or what’s the habitat of the [lost] bird, or the behavior of the bird, then not much can be really done to preserve it,” points out Jhonathan Miranda, a Venezuelan university student who works for the nonprofit group Provita and has led the ground search for the antpitta.

Those are exactly the sorts of information gaps that researchers have been working to fill for Brazil’s Blue-eyed Ground-Dove. With funding from Rainforest Trust, the conservation organization SAVE Brasil set out to assess whether the bird was under imminent threat. Fortunately, the corner of cerrado where it lived turned out to be too rocky for farms, says SAVE Brasil Executive Director Pedro Develey, “so we have a little time.”

Researchers have used that time to identify other suitable Blue-eyed Ground-Dove habitat, with the help of computer models and satellite images. Early surveys of new sites have so far come up empty, but about a dozen Blue-eyed Ground-Doves have turned up in the general area around Bessa’s 2015 discovery. And in April, a graduate student named Bruno Rennó began a field project studying the rediscovered population, with the support of Fundação Grupo Boticário, SAVE Brasil, and others. Over the next year, he hopes to nail down some basics about the doves’ lives and habits.

Meanwhile, SAVE Brasil and Rainforest Trust have raised much of the money necessary to buy the 640 hectares where the Blue-eyed Ground-Dove was rediscovered as a private reserve. The find also generated momentum for a pre-existing community-supported proposal for a nearby 30,000-hectare public reserve.

Whether those considerable achievements will be enough to help the species, though, will depend on what Rennó and others actually find out about the cobalt-eyed doves. As Schulenberg points out: “A lot of ground-doves are semi-nomadic. If it’s tracking some resource, some plant that seeds only at particular seasons in particular places,” then the species may need a larger landscape to roam across than the reserve actually covers. “If it’s literally 12 to 15 birds left,” Schulenberg says, “the prognosis in the wild is terrible.”

Develey is hopeful that bird watchers will turn up more doves, and that the private reserve will be formally established by the end of this year. But not all habitat protection efforts for Lazarus birds go as smoothly. SAVE Brasil has been working with local government officials for more than 10 years without resolution to secure a public reserve for the spectacular Cherry-throated Tanager, rediscovered in the country’s heavily cut Atlantic forests in 1998. Political turnover, local opposition, and lack of resources have all been obstacles to government protection, Develey says, though a local company is completing a 1,500-hectare private reserve. And even now, scientists still know next to nothing about the bird. It lives high in the canopy, which makes it difficult to study. And it may number fewer than 40 individuals, making it hard to know whether the current conservation strategy is working.

Still, Lima, who is working on the so-far-unsuccessful Kinglet Calyptura search with the help of ABC funding, is optimistic about the bigger picture.

“Finding the bird is just one of the results of the project,” he says, pointing to a major Brazilian television network’s recent segment on the species. “Imagine that no one ever heard about Kinglet Calyptura, and then, after a Saturday 10-minute program, millions of people in Brazil know what a Kinglet Calyptura is, and how the bird is going extinct because people destroy the environment.

“We’re trying to make these birds visible,” he says, because people won’t value something if they don’t even know it exists.

As an Observatório de Aves hashtag campaign puts it, #esqueceréextinguir.

Forgetting is extinction, too.

Sarah Gilman is a freelance writer based in Oregon. Her work has appeared in High Country News, where she is a contributing editor, as well as Nationalgeographic.com and Audubon.org.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you