Why Don’t Some Warblers Nest Farther West? Maybe It’s Just Too Tough to Get There

By Kathi Borgmann

May 18, 2017

This article also appears in the Spring 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

A flip through the range maps in any field guide shows blocks of color indicating where a species spends its summers, winters, and points in between. But why does a species occur where it does? What limits its range? People have debated this idea for at least a century—the field even has its own name, “biogeography.” And recently David Toews, a postdoctoral associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, added a new idea to the list.

Toews looked at the ranges of North American warblers and noticed an interesting pattern. More than half of these brightly colored songbird species breed in the boreal forest, where they take advantage of an incredible abundance of food during the summer months. Stretching from eastern Maine, straight across Canada and into Alaska, the boreal forest supports an estimated 3 billion birds and is often called North America’s bird nursery.

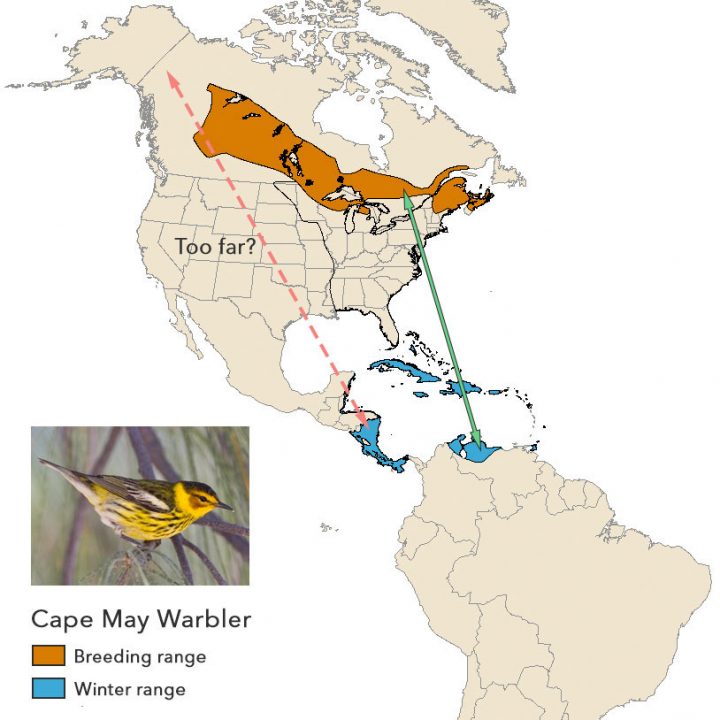

Yet even though the boreal forest offers more than 1.2 billion acres of habitat and lots of food, some warbler species use only part of it. Cape May Warblers, for example, forage and nest in spruce and fir trees, which occur across the entire boreal forest. But good luck seeing a Cape May Warbler west of Alberta, Canada. “Those places, particularly in the summer, are just jam-packed with food,” Toews says. “So presumably those would be, at a very superficial level, good habitat for these birds.” If the right kind of habitat is there, why don’t they breed there?

To explore this age-old question, Toews took advantage of the biggest citizen-science dataset on birds available. He used eBird data to look at where people reported 17 warbler species from Newfoundland to Alaska. Four of the 17 species occur all the way across, but 13 species mysteriously stop partway. Wondering if perhaps some aspect of the forest habitat was different in western Canada and Alaska, Toews looked at land cover data and climatic variables for the entire boreal forest. The results backed up his impression: appropriate habitat does exist in northwestern Canada and Alaska, even though the birds themselves are nowhere to be found.

The Cape May Warbler's breeding range abruptly stops partway across Canada, even though suitable habitat exists through Alaska. A new study suggests these birds, and several other warbler species, may simply be unable to migrate that far in time for breeding to begin. Photo by Chris Wood.

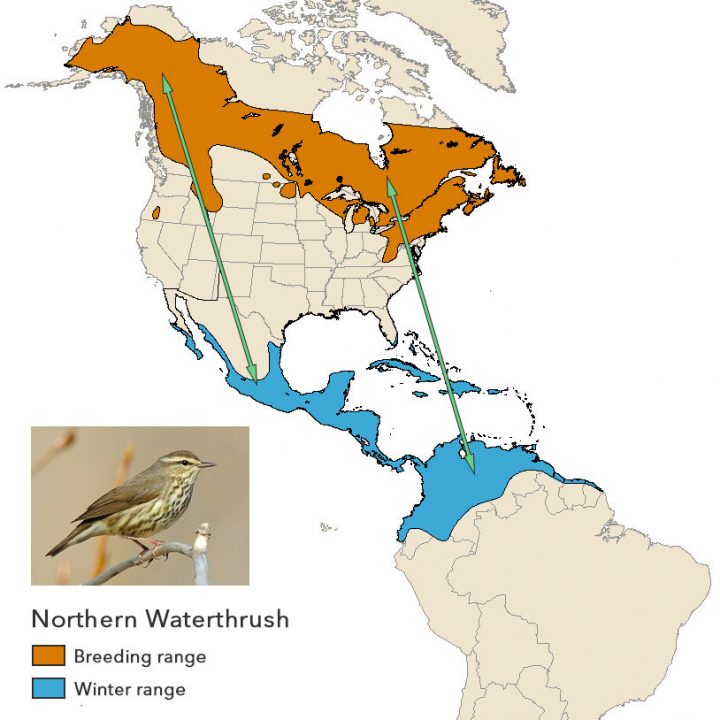

Unlike Cape May Warblers, Northern Waterthrushes breed all the way across the boreal forest. This may be because their wintering range includes western Mexico, which puts these migrants within range of western Canada and Alaska. Photo by Gerrit Vyn.

Toews thinks the answer might have less to do with the right type of habitat and more with migration distance. For a Cape May Warbler that spends its winters in Central America and the Caribbean, flying to eastern Canada takes a lot of energy. But it takes even more to reach far northwestern Canada. That extra distance might just be too much for these tiny birds. In other words, the cost of migration might limit their breeding range.

Blackpoll Warblers, on the other hand, are super migrators; they fly more than 1,800 miles one-way from South America to Canada and breed across nearly the entire boreal forest from east to west. So why can Blackpoll Warblers make the distance while other warblers can’t? “The how and why we really don’t know,” Toews says, “but the ability to store and use fuel efficiently if you are moving long distances can be a pretty important limiting factor.” Maybe Blackpolls are doing something different that Cape May Warblers, for example, can’t do, “the idea being that there are tradeoffs with some of those adaptations.”

Perhaps Blackpoll Warblers are just migration overachievers—not really comparable to other species. But there’s still the case of the Northern Waterthrush, Toews says. It winters in Mexico and Central America and nests across the entire boreal forest. Unlike the Cape May Warbler, the Northern Waterthrush winters in western Mexico. Individuals wintering there can fly straight north to western Alaska, keeping their total travel distance down to something manageable.

They’re not migrating any farther than Cape May Warblers, they’re just starting from a different location, and using the Pacific Flyway, a migration corridor that runs up the western edge of the continent. “While there isn’t a perfect one-to-one tradeoff between distance traveled and how far north a bird can breed,” Toews says, there are other navigational barriers and costs that may keep those other 13 species he studied from reaching northwestern Canada and Alaska.

Toews’ new proposal joins a number of previously suggested explanations for why species have range limits, including competition among species, geographic barriers such as the Rocky Mountains, and physiological limits such as a bird’s ability to cope with temperature extremes. “I definitely don’t think that we know the exact answer,” Toews says, “but it’s a different way to think about range limits in birds.”

Reference

Toews, D. P. L. 2017. Habitat suitability and the constraints of migration in New World warblers. Journal of Avian Biology 48:001–010.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you