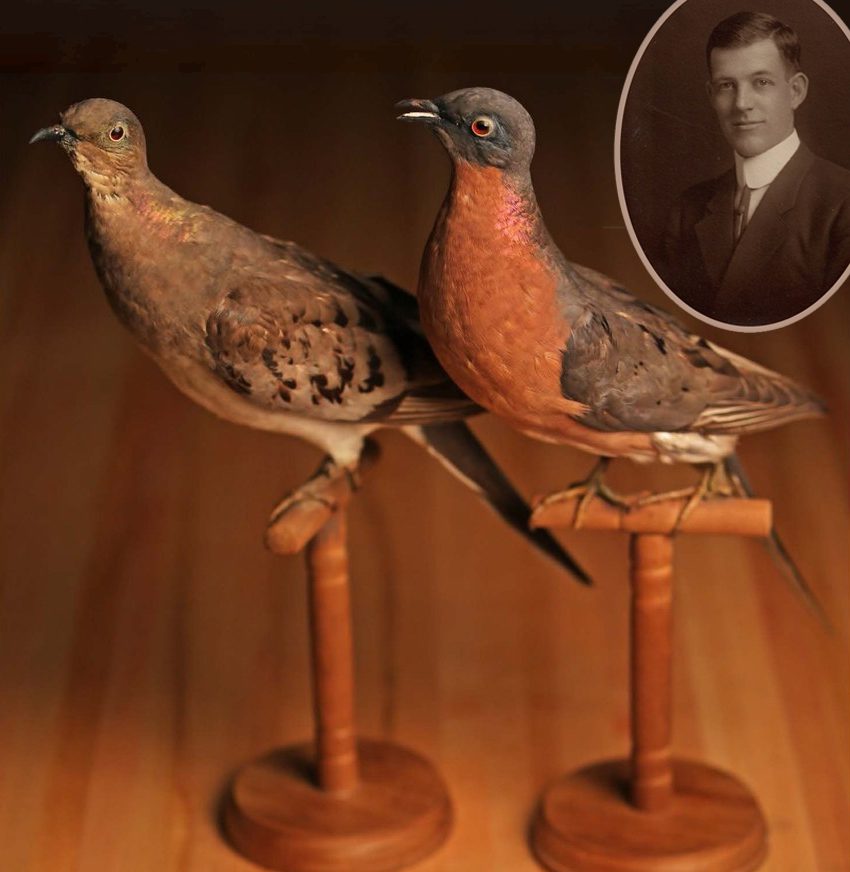

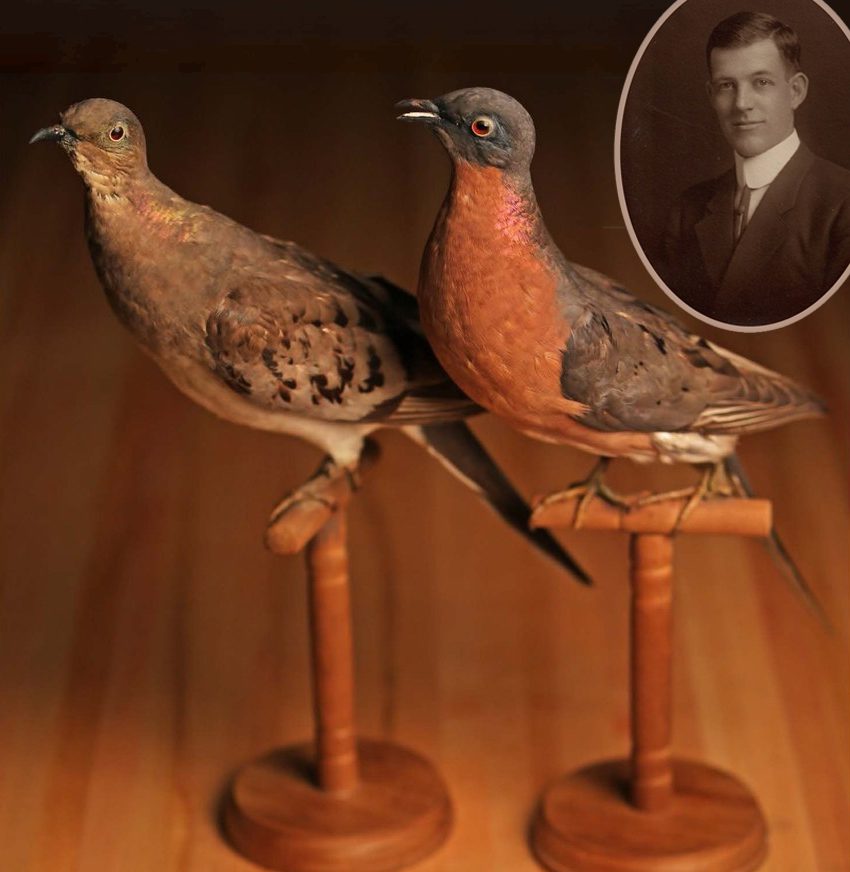

One Man’s Passion for the Passenger Pigeon

By Stanley Temple

July 15, 2015

For a bird that’s been extinct for a century, the Passenger Pigeon had a pretty good year in 2014. Books, articles, editorials, films, lectures, exhibits, plays, songs, poetry and even visions of resurrecting the species commemorated the centenary of its extinction. School children folded origami Passenger Pigeons by the thousands, and artists painted and sculpted images of the long-lost bird. Informing all those reminders of the tragedy was the lifework of a too-often forgotten natural historian who quite literally “wrote the book” on the species.

Arlie William (Bill) Schorger’s award-winning 1955 book, The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction, has for 60 years been the go-to source of factual information on the bird. His obsessive fascination with the species spanned most of his life and dated back to the time of the bird’s final spiral to extinction. For his book and over the span of several decades, he doggedly searched hundreds of thousands of documents and extracted insightful details from nearly 10,000 eyewitness observations of Passenger Pigeons (most viewable at Project Passenger Pigeon). The earliest record was the explorer Jacque Cartier’s 1534 account of “an infinite number” of pigeons flying over Prince Edward Island. Reflecting the diligence of his historical research, the bibliography of his book contains nearly 2,200 references. In spite of all that Schorger contributed to our understanding of how the continent’s most abundant bird was driven to extinction, his name was mentioned infrequently amid all the attention to the 2014 centenary. This, then, is Bill Schorger’s story.

Born in 1884 in northern Ohio, Bill developed his fascination with natural history at an early age. He credited his uncle for instilling in him a keen sense of wonder about nature and for introducing him to the Passenger Pigeon.

“One of my earliest childhood recollections is walking with my uncle on what was then called the old military road. He mentioned that this road once ran through a large forest of beech and oak instead of bare fields. When he was young flocks of wild pigeons would fly over in spring and autumn in such numbers that the sun was darkened and the sound was like that of falling water. Men stood in that narrow slit in the forest firing shot after shot into the passing flocks until their guns became too hot to load. Beautiful birds with blue backs, their wine colored breasts now flecked with crimson, fell earthward like ripe fruit. The gaping holes in the ranks closed instantly and the flocks streamed on and on. When the beech bore nuts the pigeons would alight on the ground to feed. As the food was exhausted, the birds in the rear flew to the front of the line so that a living wave of blue passed continuously over the forest floor. The leaves fanned by a thousand wings rose heavenward to fall gently in the path of the receding tide. He told me ‘Men said that you could kill and kill for their numbers were inexhaustible, but we shall never see the like again.’ I heard all this and wondered. Then I was told that the pigeon was no more…I could never think of the extinction of this bird without indignation. It seemed at the time, even to a young boy, so thoughtless and unnecessary.”

Bill acquired his first bird book, Chapman’s Handbook of the Birds of Eastern North America, in 1905 while he was an undergraduate at Wooster College in Ohio. He became a bibliophile, and his personal library of ornithological works, housed at the University of Wisconsin, would eventually grow to over 2,000 items, one of the largest personal collections in the country.

After earning a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Wisconsin, Bill Schorger stayed in Wisconsin and pursued a professional career as a research chemist and businessman. He became an authority on the chemistry of cellulose and wood, and his new ideas and products resulted in 41 patents that enriched him and his companies. His success as a businessman allowed him to devote increasing amounts of time to pursuing his personal passions. A veritable polymath, he made significant contributions to many endeavors besides chemistry and business, including ornithology (Founder and President of the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology), history (President of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters), conservation (Board of National Audubon Society), literature (President of the Friends of the University of Wisconsin Library and the Madison Literary Club) and public service (Wisconsin Conservation Commissioner). After his 1951 retirement from the business world, he began a second career on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin’s wildlife department where he remained active for the rest of his life. Although his stoic demeanor may have initially intimidated some wildlife students, they soon learned to appreciate his dry sense of humor as well as his methodical, obsessive nature as a scientist.

Bill excelled in a niche that was defined by his most significant contributions to science: gleaning fascinating bits of natural-history knowledge from eyewitness accounts in a plethora of historical documents, including journals and diaries of explorers and travelers, government reports, books, journals, and newspapers. In tireless pursuit of records of wildlife in early America he would eventually spend more than half his life making regular—in many years almost daily—visits to libraries, archives, and museums to seek new material. A librarian once told him: “I have moved more tons of papers for you than for any other 10 persons in Wisconsin!” Schorger countered that, owing to the accumulation of library dust, his laundry bill was excessive. In an era before copying machines were available, he carefully transcribed by hand each new finding into his ever-growing collection of research notes, which eventually totaled around 25,000 pages. His approach was somewhat similar to that of his contemporary, Arthur Cleveland Bent, who spent decades assembling his 21-volume Life Histories of North American Birds. As a result, “encyclopedic” was a term often used to describe the breadth of knowledge accumulated by these two ornithologists. A diligent correspondent, Schorger exchanged letters with nearly every ornithologist of his time, including Cornell Lab founder Arthur Allen.

Reflecting norms among natural historians during his formative years, Schorger engaged in two practices that have all but vanished today: keeping detailed journals that recorded his times in the field and collecting voucher specimens. Probably influenced by his schoolboy exposure to Cornell University’s Nature-Study Leaflets, which encouraged journaling, he began keeping detailed field notes in 1909 when he moved to Madison. His field journals totaled 1,645 tersely written pages by the time of his death in 1972. Entries from his regular birdwatching excursions and his reviews of historical records eventually yielded enough information that by 1931 he was able to write his first major ornithological paper, The Birds of Dane County, Wisconsin. It was while preparing that paper that his signature research into historical records began in earnest. He followed up by writing a series of 28 papers entitled “The History of [fill in the blank with the name of a species] in Early Wisconsin.” Over his lifetime, he authored around 280 publications that reflected his eclectic intellectual pursuits.

His field notes and copious research records reveal that he rarely collected data that were intended to test some preconceived hypothesis. Instead, he recorded interesting observations he made in the field and noteworthy life history details he discovered in the library, often over the span of many years. He then retrospectively pored over his notes to see if he could make sense of nature by discerning interesting patterns.

One example involved his tedious, and some might say eccentric, observations of road-killed birds. He made regular trips from Madison, Wisconsin, to Freeport, Illinois, from 1932 to1950. In his field journals, he recorded details of every road-killed bird he found and examined along the 70-mile mostly rural route. In 97,020 miles of driving, he recorded 4,939 road-killed birds, representing 64 species; among them were 2,784 House Sparrows, 389 Red-headed Woodpeckers, 310 American Robins, 271 Ring-necked Pheasants, 235 Eastern Screech-Owls, and 230 Northern Flickers. After reviewing his 18 years of journal entries, he was able to detect several patterns revealed by the frequencies with which species were being killed: some species were declining, some were increasing, some were killed disproportionately to their regional abundance, and some were killed in specific highway situations. As always, he dutifully documented the results of his curious investigations, and in 1952 he published a now-classic paper, “A Study of Road Kills.”

Although many today would admire his conscientious journaling, they might take exception to his old-fashioned insistence that a rare-bird sighting should be verified with a collected specimen. Indeed, even in his day, Schorger was often at odds with his fellow Wisconsin birders. When a Brown Pelican showed up on Madison’s Lake Mendota, Schorger knew immediately that it was the first state record of the species. The drama that followed is legendary in the Wisconsin birding community. As local birders converged to see the rare bird they instead encountered Bill Schorger with his shotgun over one shoulder and the dead pelican over the other. At meetings of the local Kumlien Bird Club, he challenged every sighting of a rare bird that wasn’t backed by a specimen. Club members recalled being so intimidated that they were often reluctant to report an unusual sighting until they had a thoroughly convincing response to what they knew would be coming. There was, however, never any doubt about the identification of rarities that Schorger discovered. The University of Wisconsin bird collection contains 453 of his skillfully prepared specimens!

When Bill became fascinated with some obscure aspect of natural history, his zeal for uncovering details was irrepressible. One of his quests involved uncovering the history of the puma in Wisconsin, and he became obsessed with finding the last known specimen collected in the state. He discovered that it had initially been deposited in a museum in Appleton, Wisconsin, but that it had later been discarded. After much detective work, in 1958 he finally traced it to a seedy bar in northern Wisconsin. Intent on obtaining the specimen, he talked the bar owner into relinquishing it for $50. The dilapidated cat, reeking of beer and cigar smoke from its decades in the bar, was donated to the University of Wisconsin. For a brief time, it was even recognized as being an example of an extinct subspecies, appropriately named Felis concolor schorgeri!

His 1955 Passenger Pigeon book and his 1966 follow-up book, The Wild Turkey: Its History and Domestication, are considered to be classics in wildlife literature. With self-effacing dry humor, Bill wrote to a complimentary reviewer: “Having read your review of the book on the wild turkey, I have decided to buy a copy.” The Passenger Pigeon book earned Schorger the 1958 William Brewster Memorial Award, which is given annually by the American Ornithologists’ Union to recognize an outstanding contribution to the literature on birds of the Western Hemisphere. Well respected by the ornithological community, he was elected a Fellow of the American Ornithologists’ Union in 1951.

One of Bill Schorger’s little-known, behind-the-scenes undertakings played a pivotal role in the emerging field of wildlife management. When Aldo Leopold was transferred to Madison, Wisconsin in 1924 to become Assistant Director of the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Products Laboratory, he met wood chemist Bill Schorger, and the two became close friends, often hunting and bird watching together. After Leopold resigned from the Forest Service in 1928 to pursue his interests in wildlife conservation, Bill Schorger and a few of Leopold’s other influential friends in Madison began lobbying the University of Wisconsin to give the up-and-coming wildlife conservationist a faculty position. But it was a hard sell. The Great Depression had hit the university’s budget hard, Leopold had no Ph.D. or teaching experience, and his growing reputation was in a field that had never before been recognized in academia. Rising to the occasion, Bill Schorger and others made the university’s 1933 decision to hire Leopold easier by quietly donating funds to cover his salary for 5 years. In 1938, when Leopold was offered the position of Director of the U.S. Biological Survey (the predecessor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), Schorger and his co-conspirators again lobbied the university, this time to retain Leopold by offering him his own department. Leopold decided to stay at the university as chair of the first academic department in the world devoted to the new field of wildlife management, but his stellar academic career might never have happened without a little help from his friends.

Bill Schorger’s legacy includes descendants who, through three generations, have been inspired by and shared his fascination with nature and commitment to conservation. A generous endowment supports wildlife research and maintains his library at the University of Wisconsin. Bill once commented, “At intervals throughout my life I have been plagued by the thought that I was born a hundred years too late.” Although that fate deprived him of the opportunity to see a living Passenger Pigeon, his meticulous and obsessive quest to discover everything that was known about the bird will continue to be the most complete account of the natural history and extinction of this iconic species.

While occupying the faculty chair once held by Aldo Leopold at the University of Wisconsin, Stan Temple frequently mined Bill Schorger’s trove of historical data. Bill Schorger’s grandsons, Jock Schorger and Bill Schorger, inspired this article.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you