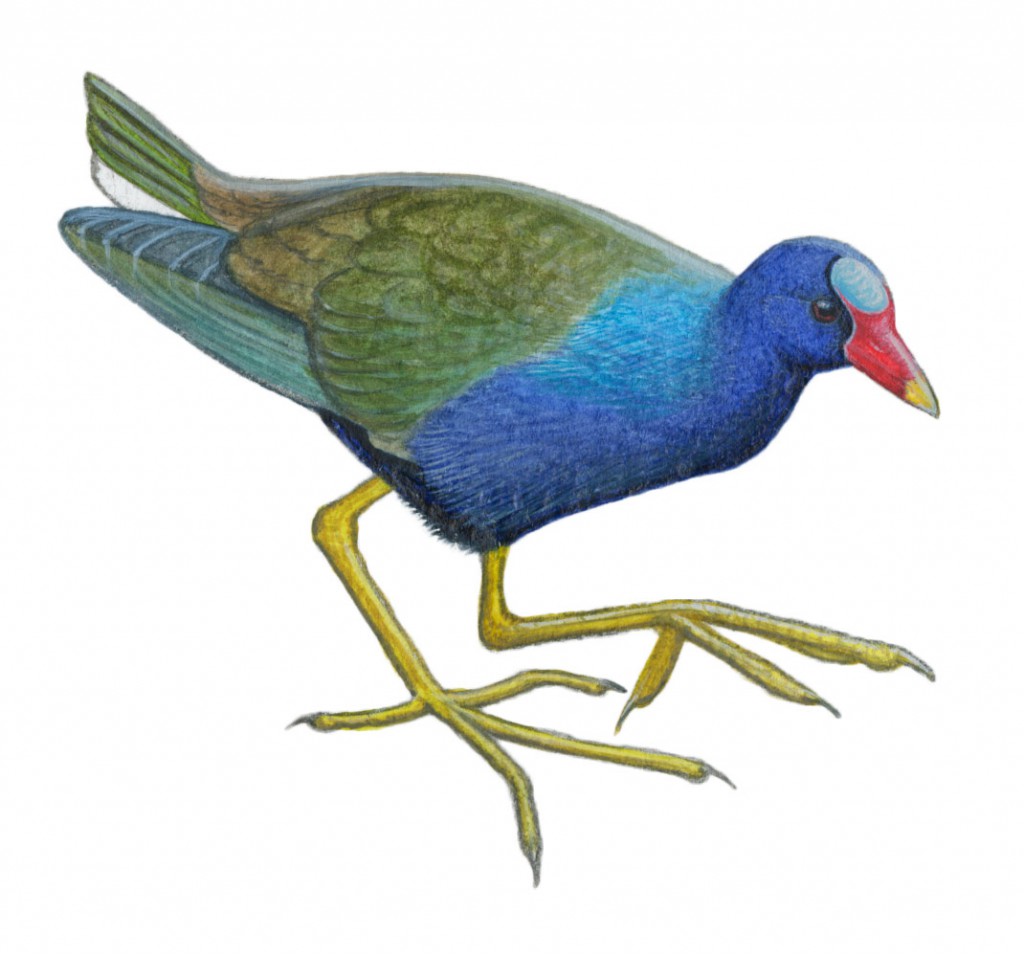

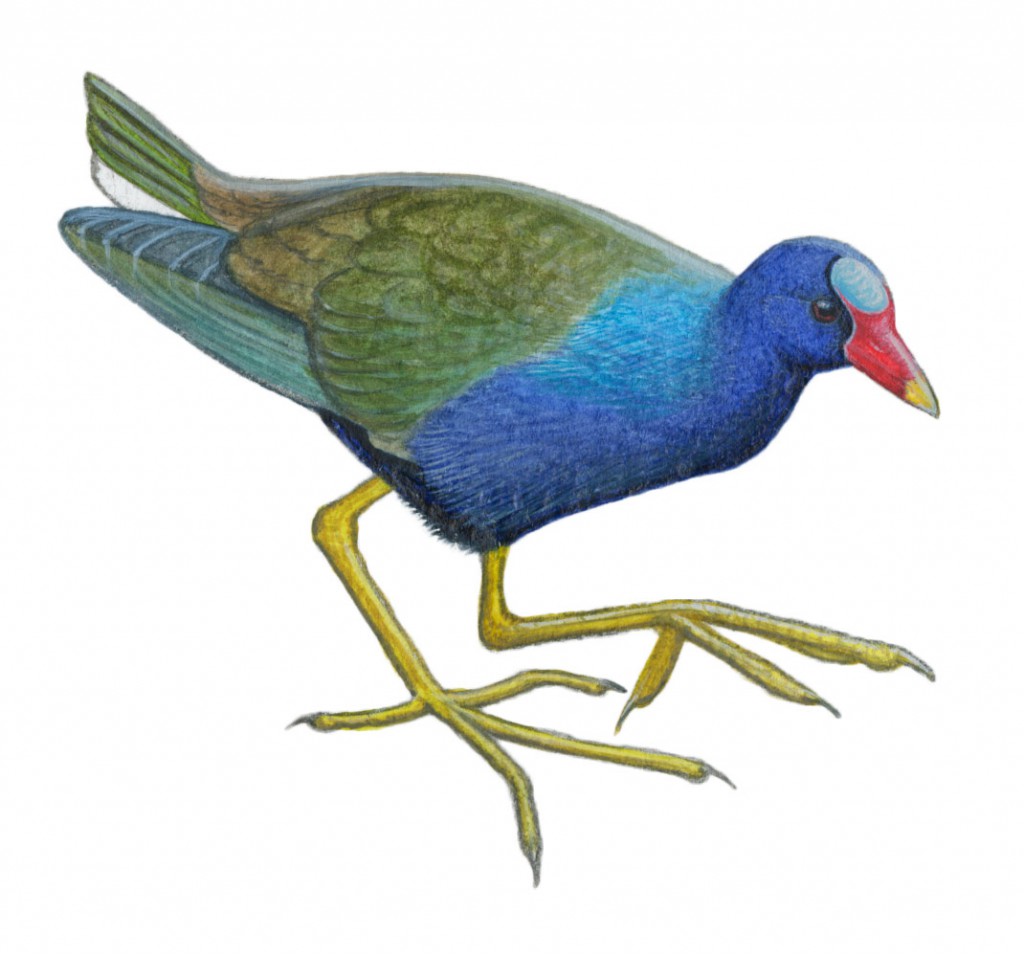

Eight Intriguing Migration Mysteries Solved With BirdCast and eBird

Artwork by Luke Seitz October 9, 2014

Scientists are learning more than ever about autumn bird migration, but there are still plenty of unsolved mysteries. What forces dictate their departures and arrivals? Why do they choose the routes they do? And why do some birds end up far off course?

In the past, rare sightings have been chalked up as vagrants—anomalies of bird movement that couldn’t be predicted and might never happen again. But as time and data points have piled up, it’s become clear that many rare sightings are the result of regular, if infrequent, patterns. As we gain an understanding of these patterns, we can use them to unravel migration mysteries and know when and where to look for rarities.

Two of the programs leading the way in this effort are BirdCast and eBird. The eBird project provides the raw sightings data (when bird watchers like you report your sightings to the project). BirdCast combines the sightings data with meteorological data and weather surveillance radars (which can “see” birds just as they can “see” raindrops—as in the map above). These data sources allow BirdCast’s team to develop weekly, region-specific predictions to let North American birders know which birds to look for and when—as well as to understand rarer phenomena like these eight migration mysteries:

What’s that “peep” in the night? Ever go outside on a crisp September evening and hear what sounds like a spring peeper in the sky? Except, it’s fall… and frogs don’t fly? Lots of songbirds migrate at night and call to each other with very short, faint notes. The calls of Swainson’s Thrushes are among the most distinctive of these “night flight calls,” and they are loud enough that you can actually hear the birds as they fly overhead. Your best bets for hearing this peep in the night sky will come immediately after a cold front passes, particularly when birds fly into areas with poor visibility (like fog) and light pollution where calling increases dramatically (birds tend to call more frequently when disoriented). See this post to hear the call notes and learn how to identify them.

Where did all the Blackpoll Warblers go? Blackpoll Warblers are fairly common spring migrants all the way up through the eastern states. Not so in fall, when they are rarely sighted in states south of the mid-Atlantic. That’s because their main fall migration route takes them out over the open ocean. The birds often fly nonstop over the Caribbean en route to their winter grounds in South America.

What’s a Blue-footed Booby doing in California? The Golden State boasts a huge collection of cool birds, but the Blue-footed Booby is not usually one of them. It’s a tropical seabird typically found along the Mexican coast and south to South America—but in fall of 2013, many dozens of Blue-footed Boobies were reported along the California coast. When the BirdCast team looked into meteorological patterns, it appeared that unusually warm sea surface temperatures may have caused the move, along with a similar pattern in Elegant Terns. The suggestion is that prey fish moved north to find cooler waters, and so the boobies moved with them.

Why do Long-billed Curlews winter in both California and Mexico? Long-billed Curlews breed in grasslands and open country of the central and western U.S. In winter, you can find them in coastal and interior California, as well as in landlocked wetlands of the Southwest and Mexico. By putting together species distribution models from eBird data, it appears these two populations may employ different migration routes. Curlews from the Great Basin may travel westward to winter in California, while Great Plains curlews travel south to reach Mexico.

(Illustrations by Luke Seitz. BirdCast is a joint project of computer scientists and bird biologists at the Cornell Lab, Oregon State University, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and other partners.)

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you