A Modest Proposal: Can eBird Help Choose Better State Birds? [Part 1]

We love cardinals, mockingbirds, and meadowlarks, too—but do these 3 species have to represent 18 separate states? We turned to eBird to find alternative state birds with data to back them up.

April 5, 2023

From the Spring 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the 13 provinces and territories of Canada have official birds. A campaign in the 1920s by the General Federation of Women’s Clubs got the ball rolling, and over the course of the 20th century state and provincial governments used acts, proclamations, or in some cases the strength of tradition to come up with their bird of honor.

State birds are meant to pay tribute to local wildlife while inspiring people to get to know their avian neighbors. But for birders, some of the official state and provincial birds are a bit, say, uninspiring—and there’s an amazing amount of overlap. Only 20 out of 50 states have unique state birds. Seven states share the Northern Cardinal, six claim Western Meadowlark, and five honor Northern Mockingbird. Even among the unique state birds, there are exotic species (such as Ring-necked Pheasant of South Dakota) and domestic chickens (like the Rhode Island Red).

A birder might ask: With more than 700 native bird species to choose from, is the current selection of state birds really the best that our societies can come up with? (In fact, Nick Lund, aka “The Birdist,” tackled just this question in a hilarious 2013 post State Birds: What They Should Be on his blog.)

A Thought Experiment, with eBird Data

As it happens, the eBird Status and Trends project provides a great, scientifically grounded basis for finding unique connections between states and the birds that live there. Based on hundreds of millions of citizen-science records, as well as sophisticated computer models that use land-cover data from satellites, the eBird Status and Trends project can estimate how much of a bird species’ global population occurs in each state or province at a given time of year.

More State Bird Suggestions

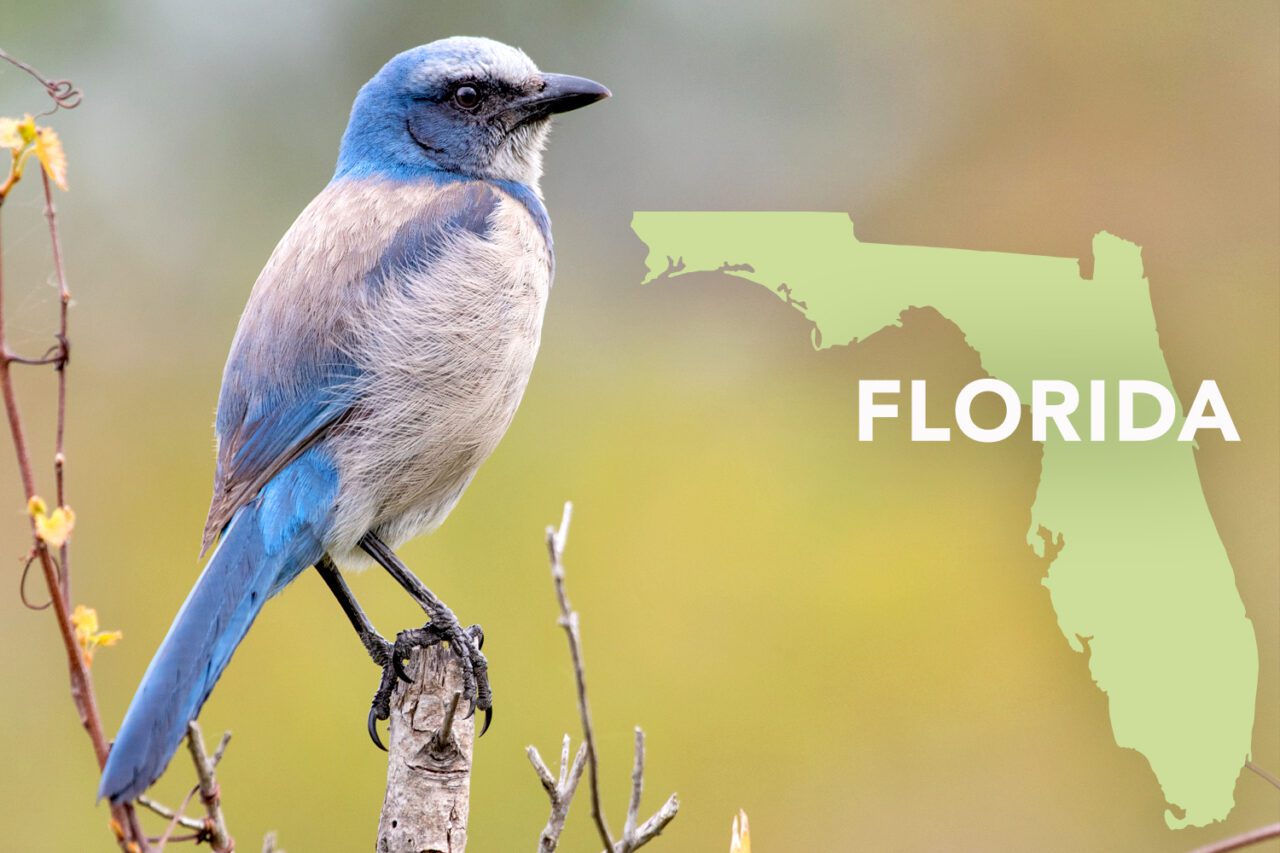

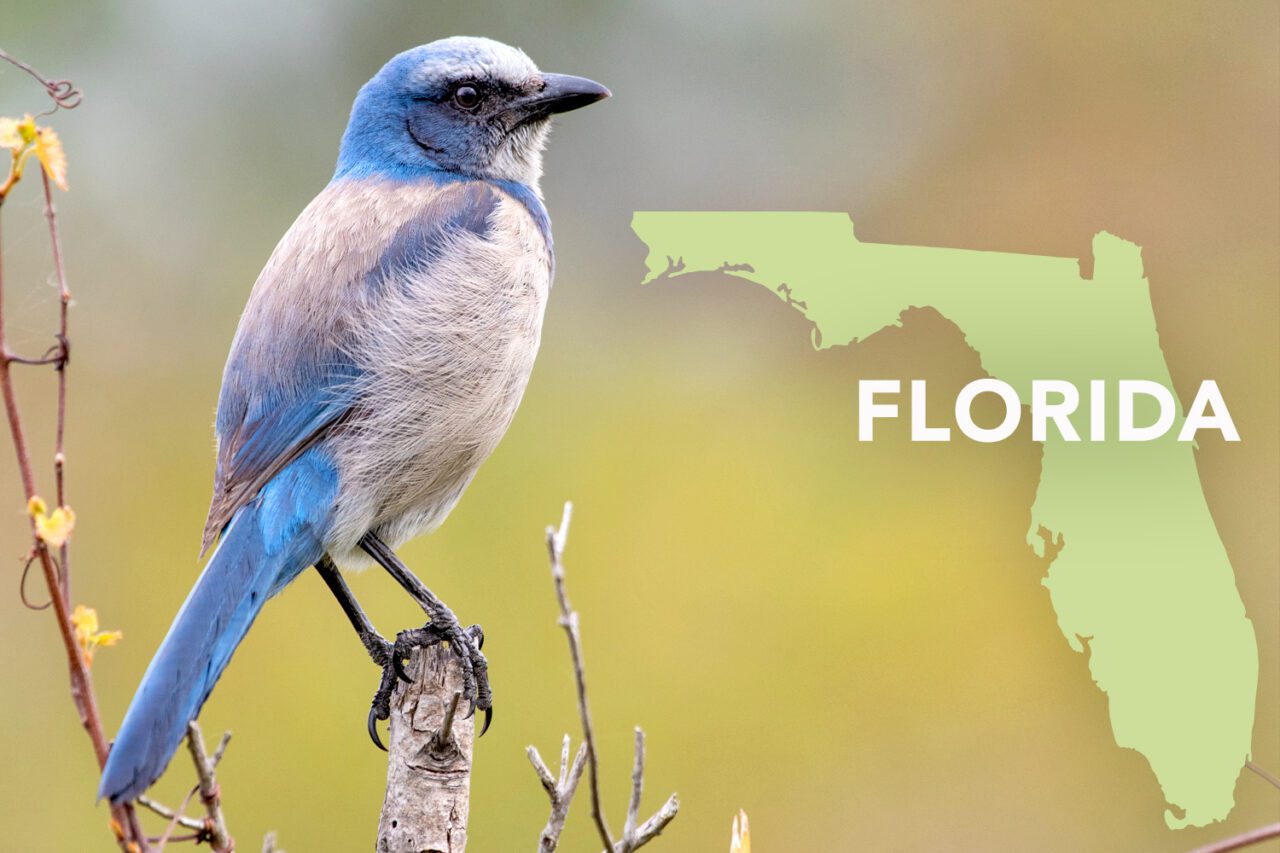

This data can help pinpoint a well-suited bird for each state or province by showing which regions host globally significant populations of certain species. The best candidates for these new, scientifically informed suggestions are species with rock-solid claims. Florida, for example, hosts fully 100% of the global population of the endemic Florida Scrub-Jay—isn’t that a good reason to nominate it as the state bird?

This analysis prioritized breeding-season stats—such as the proportion of a bird’s global population that’s found in a state, or its population density. In cases where no species had an especially strong claim during breeding season, migratory and overwintering populations were considered. Delaware, with its famous springtime concentrations of Red Knots, is an excellent example.

Above all, the analysis sought to identify a different bird for every state and province. (In other words, no repeats.) By identifying each state’s or province’s most biogeographically characteristic birds, this method casts a spotlight on the region’s distinctive landscapes and ecosystems.

Some of these selections are sure to spark controversy. For starters, four of our state bird suggestions are species named after other states. (The data makes a strong case that Kentucky Warbler should be the state bird of Arkansas, for example. How Kentuckians and Arkansans feel about it remains to be seen. ) The list also bypasses some long-established sentimental favorites, such as Maryland’s Baltimore Oriole. And no matter how strongly the data suggests replacing New Mexico’s Greater Roadrunner with the biogeographically unique yet little-known Chihuahuan Raven, we recognize it’s a steep uphill climb.

Still, in some small way, this challenge to the status quo might encourage people to reconsider and ponder their relationships with their local birds. In any case, it’s a fun thought experiment. So if you’re curious, take a look at what the official state and provincial birds might be, if they were determined by eBird.

Part 1: States That Finally Get Their Own State Bird

Just three bird species hold the state bird slot for a remarkable 18 states (Northern Cardinal for 7 states; Western Meadowlark for 6 states; Northern Mockingbird for 5 states). And none of those three show up on a data-driven list of eBird state birds. Cardinals, meadowlarks, and mockingbirds were likely popular candidates as state birds because of their widespread occurrence and familiarity, but since these are common birds that occur in many states, there is no state in which their population rises to a globally significant level. Here’s a suite of suggestions for birds that really do represent their states.

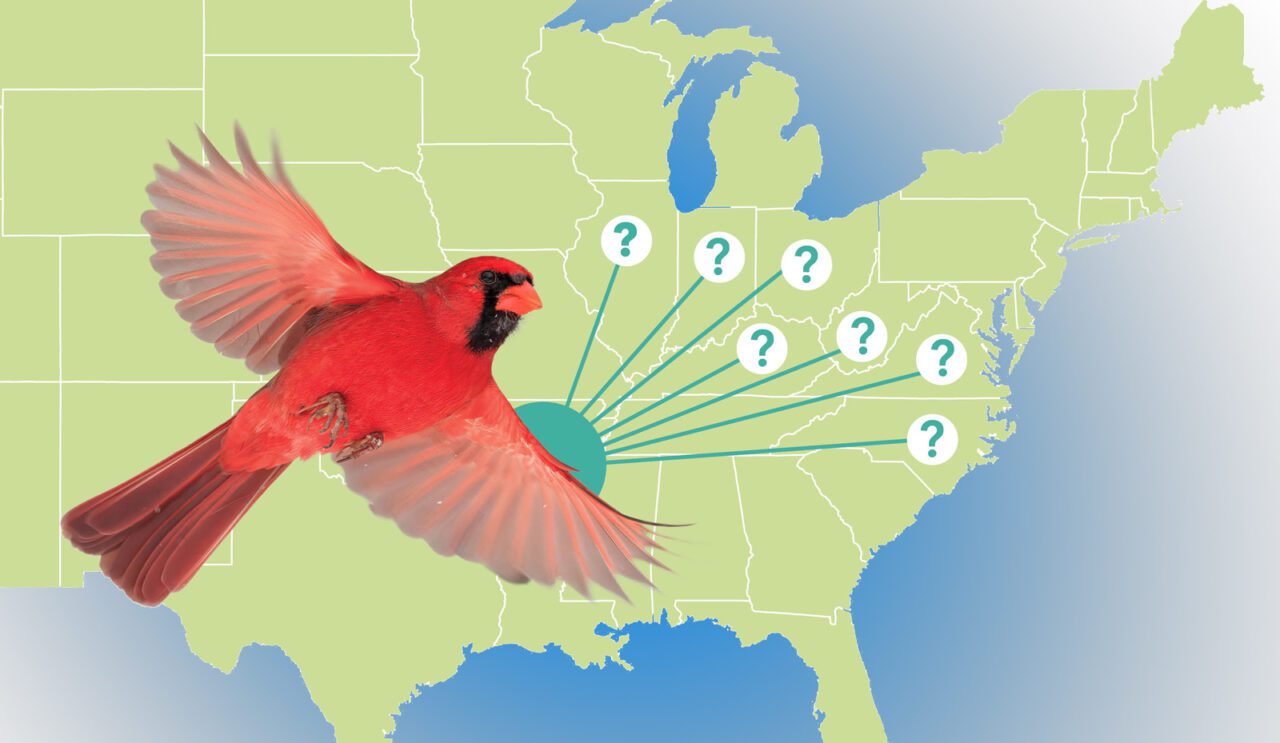

An Alternative to America’s “Cardinal Belt”

Seven contiguous states from the Midwest to the East Coast are currently represented by Northern Cardinal as their state bird. There’s no denying the mass appeal of the beloved “redbird”—it’s been the most-visited page in our All About Birds species guide every year for the last 10 years—but what about letting a few other species share the spotlight?

eBird data offers a way to pinpoint species that have a unique biogeographic connection to each state. Case in point: the Cerulean Warbler has a special claim to West Virginia, which is home to more breeding Ceruleans than anyplace else in the world, 26.7% of the global population. Cerulean Warbler was cited in the 2022 State of the Birds report as an “On-Alert” species that has lost half its population in the past 50 years. Its global population has declined by 70% over the past five decades, yet it is still abundant enough (especially in places like West Virginia) that it is not yet federally protected. Raising awareness of the Cerulean Warbler in the heart of its range could spark heightened awareness and conservation efforts to keep this bird off the Endangered Species list.

eBird data uncovered these suggested alternatives for the rest of America’s “Cardinal Belt”:

Giving the Western Meadowlark a Run for Its Money

The Western Meadowlark is a colorful member of the blackbird family and is found across western and central North America. Its cheerful song rings out across its territory, where it’s often found foraging on the ground, in open grasslands, meadows, fields, or along marsh edges. Six states share the Western Meadowlark as their state bird, but eBird suggests these other species are also worth a moment of consideration:

Five Options for the South’s Beloved Northern Mockingbird

Five states arrayed across the southeastern U.S. all claim the Northern Mockingbird as state bird. Their vocal prowess is indisputable, but surely there are a few gems among the South’s vibrant birdlife that could be recognized instead.

In December 2022, for example, Florida state representative Sam Killebrew filed legislation to crown the Florida Scrub-Jay as the new official bird for the Sunshine State. Similar efforts have failed in the past. John Fitzpatrick, Florida Scrub-Jay researcher and former director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, says he has high hopes for the bill’s passage this time around: “I strongly favor switching from the ho-hum, occurs-everywhere Northern Mockingbird to the charismatic, state-endemic Florida Scrub-Jay. … Seeing this remarkable and world-famous bird is a sublime privilege that is unique to the state.”

Here are the other mockingbird alternatives that our eBird analysis settled on:

Matt Smith is an applications programmer for the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Smith conceptualized this story while playing with eBird data as a hobby. Marc Devokaitis is the associate editor of Living Bird magazine.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you